Last time I enthused about the power of the Google Ads Campaign Drafts and Experiments architectural framework. This week, I’ll suggest five experiments to try.

I’d love to hear about your own unique experiments, too!

In terms of setup, as alluded to previously, the process will often be about the same. You outline a key change or “big idea” you want to test to see how it will really, no foolin’, affect your core KPI’s (Key Performance Indicators) such as total revenue, cost per acquisition, impressions (if you go for that sort of thing), and so on, across a campaign. Remember to modify columns in the Campaign Experiments Dashboard to highlight the ones you see as key criteria for success. Since most advertisers’ objectives boil down to ROI and revenue – and there is generally a tradeoff between the two – typically you’ll be eyeballing both metrics like return on ad spend (or ROAS, also known as Conv. Value/Cost), on one hand, and total transactions (also known as conversions) or revenue, on the other. (Transaction or conversion goals may be something other than a sale, such as a lead or a phone call, of course.) All of this assumes you have reliable conversion tracking set up in Google Ads.

Try these Experiments:

1. High Bid Experiment

You’ll be bidding every keyword in this campaign (in the Experiment group, leaving the Control group as is) 20%, 25%, or 30% higher (your call). This sounds like a fairly blunt instrument. But I’ve learned a lot from this one. That’s what great experiments do. They may show you something you weren’t expecting. I call it a blunt instrument because if you had cause to bid higher on keywords, you could simply optimize and bid all your keywords to KPI targets over time. Sure, of course. The objective here is different: to uncover any magic or insights that may have escaped you using the “patiently optimize” method. To learn something more – in a big hurry, for a client that needs to find non-obvious pathways to growth.

If you’re already pretty happy with your conversion volume or revenue from this campaign, and the ROI performance is strong, what could this Experiment possibly do but fail, you ask?

Very good question. But even if the Experiment does fail, it will provide a solid answer if you find yourself repeatedly asking “Is there any room to go more aggressive?” Most of you, and your bosses or clients, have a pretty good sense what “room” means in this context. If you bid higher and you’re already bidding pretty high, you’ll be engaging in behavior I typically dislike – I call it “bidding through the top of the auction.” The effect is like pushing on a string. You spend more, but you earn the same revenue, reducing profit.

Interestingly, though, people may have been missing out on available “room” in certain cases for several reasons.

- (a) Diabolically, Google may reserve its juiciest, largest, and most credible ad unit layouts for aggressive advertisers. Sure, you show up in 2nd or 3rd ad position with bid A, but with Bid (A x 1.3), for example, you may more frequently show up in 1st ad position – and, importantly, serve more frequently with Seller Ratings Extensions and other information that not only increases your conversion rates but also volume. Were this true, you might actually (in some weird cases) see your ROI metrics increase as your spend, CPC’s and revenue increased! Kind of like win-win-Win-win-win. (I can’t count all the wins! Let’s assume that middle win was Google earning more ad revenue.)

- (b) When advertisers used to look at Avg. Pos. as a measure of whether they might soon “bid through the top of the auction,” they were often misled. Without belaboring the point here, various Impression Share metrics are more valuable guides to aggressiveness level and where the “top” may lie. Wisely, Google has sunsetted the Avg. Pos. metric. Instead, we use Search % IS and Abs. Top % IS. (To be discussed on the coming weeks.) Surprisingly, I don’t find myself missing Avg. Pos.

- (c) Quickly eyeballing any of these metrics, you may not have segmented for the same metrics on mobile devices. Whereas you had less “room” in the auction in the Computer segment, bidding higher across the board unleashes new inventory on mobile devices, where you may be currently bidding more cautiously. This isn’t always going to work. It’s more likely to work for a campaign whose products or services are generally performing strongly, and are strongly associated with your strategy or brand.

There are quite a few reasons why this Experiment can fail. But it may succeed. It will definitely teach you something. As with all Experiments, give it a good chance to achieve strong levels of statistical significance. Those details are nicely shared in the Experiments Dashboard, and further detail lurks beneath the blue asterisk (recall discussion earlier in Part 8).

2. RSA’s vs. ETA’s

Let’s say the popular theory (assuming sufficient bandwidth to get creative and do research, and assuming decent-volume adgroups) is that Google’s new Responsive Search Ad units will outperform your tried-and-true ETA’s (Expanded Text Ads, which replaced STA’s or Standard Text Ads.)

Problem: Google’s systems determine how many ad impressions (and which impressions) to apportion to multiple ads in rotation, and how many ad impressions to assign to potentially tens of thousands of possible combinations within the multivariate ad testing environment of RSA’s (go back to Part 4 for a reminder about multivariate testing; if you want a taste of how such testing is used in various industries, try Googling “The Taguchi method”).

Let’s do this, then: figure out all the RSA ad units you’d like to add to a campaign, to various ad groups. (Tip: at first, don’t add multiple RSA units to any given ad group. Pour your creative energies into the best possible creative for a single RSA for each group. It’s also OK to exclude lower-volume groups from this test. When you take advantage of the maximum number of headlines and descriptions Google allows for a single RSA unit, you are activating tens of thousands of possible combinations – not including the variance by which ad extensions may be shown over time.)

For your Experiment group, you’ll run this campaign including all the new RSA’s. The control group will contain none of the above.

I’m betting that, after a month or three, you’ll have yourself a definitive answer as to the aggregate performance of both versions of the campaign, having given each version of the campaign a fair shake.

As a smart person, I don’t need to tell you that you could do the reverse of this by creating an Experiment group for which you’ve paused a bunch of currently-running RSA’s. The control group would keep both ad types running. Either way, you get a comparison.

I don’t consider this type of experiment definitive. It’s just an idea. Try it if it seems interesting to you.

Sometimes RSA’s notably underperform and we must pause them. That’s situational, and depends on the quality of the inputs. To quote Elaine’s Dad in a Seinfeld episode: “I don’t need anyone to tell me it’s gonna rain. All I have to do is stick my head out the winda!”

3. “Does Smart Bidding really outdo so-called manual bidding?”

A human-optimized campaign can use a variety of hands-on methods to improve and refine towards targets. We can change keyword bids, view and act on Search Query Reports, alter bid adjustments such as geography, mobile type, demographics, and ad scheduling. We can also layer Audiences on top of campaigns, and adjust those bids.

Smart Bidding strategies – a feature in Google Ads (you can set it to pursue goals like Target CPA or Target ROAS, for starters) – allows Google’s machine-learning-fueled “bidding bot” (not to be confused with Googlebot, the nickname for the web crawling Google does for organic search) to tackle all of those optimization points available in the Google Ads interface. Smart Bidding also has access to some user data and patterns that we do not (such as user behavior, browser and exact device, and so on – Google conceals the exact methodology of Smart Bidding as a black box). It “learns” over time which user sessions are most likely to convert to a sale (or other goal), and can bid higher on similar user sessions. That type of predictive bidding can account for many complex pathways to a conversion, such as appearing more or less often on certain obscure queries that, via match types, match to the keywords you include in the campaign.

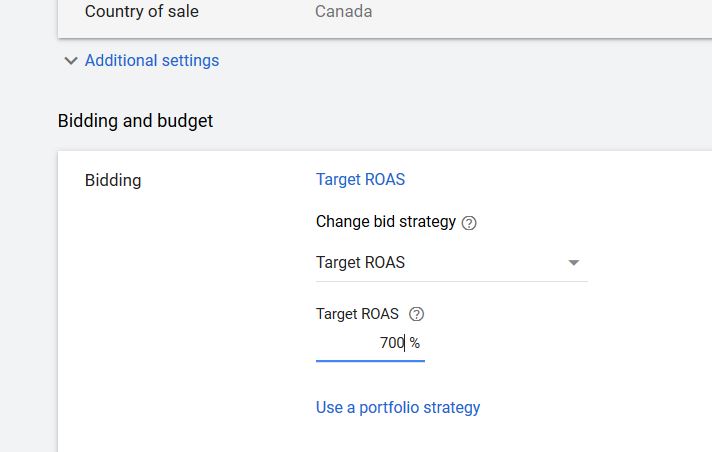

Setting a target ROAS to test its efficacy as the bidding strategy in an Experiment group.

How do we really know if Smart Bidding is improving your results? While no methodology in this fast-paced, proprietary-to-Google environment can be definitive (note that Smart Bidding could poach easy conversions using remarketing audiences – cherry-picking – or bleed unwanted conversions away from other campaigns – a process I’ve referred to as cannibalization), it’s worth running a solid test to see what significant improvements are being reported in the aggregate at the campaign level. Get your Campaign Drafts & Experiments rolling for your chosen campaign. The Control group will be employing your existing bids – ideally, ones you’ve honed for some time – using Manual CPC bidding or Manual CPC bidding with Enhanced CPC. Alter the Experiment group at Settings to set Bid Strategy to something like Target ROAS. Set your Target to your desired target, ideally somewhere just a bit more or slightly less stringent than you’ve experienced to date in the campaign (example: 240%). Check the Dashboard every so often. What you’ll be looking for is a statistically significant improvement in both ROI (eg. ROAS) and Conversions or Revenue – according to your company’s goals, of course. In a campaign with decent volume, you’ll want to run the Experiment 4-8 weeks or as long as it takes to establish a statistical winner.

In the laboratory, always keep a level head, maintain a sense of your surroundings, and keep a fire extinguisher at the ready.

4. Match Type Madness!

One of the things that bothers purists is match types that allow Google’s systems to ad lib a bit in terms of how closely user search terms may map to the keywords you’re bidding on. Today, Google allows itself some latitude on all match types, including phrase and exact match (you heard right!). But many of us began whinging many years ago, when broad match (means “user query can map to your keywords in any order, and for longer phrases, the only requirement is that all of those keywords appear somewhere in the user search query”) was “enhanced” so that a lot of additional semantic matching was also allowed under this match type (this was officially called Expanded Matching). This might help advertisers find new business, but it might also be annoying because it just isn’t what we’d come to expect that match type to do.

A match type called Broad Match Modifier (BMM) was introduced to respond to advertiser complaints around this two-faced “broad match.” This curiously-named new version of broad match might have been better dubbed “broad match classic,” as it just took us closer to the original version of broad match. It’s invoked in Google Ads campaigns by adding a plus sign to each word you don’t want to be “expanded” – in other words, the old broad match rules apply and the word matches must be exact and not “meaning-based.”

So let’s say you’re curious about how swapping a lot of these old, chimerical broad matches (undecorated with plus signs) for the stricter Broad Match Modifier versions might improve or worsen the overall, aggregate performance of your campaign on the KPI’s that matter to you. For the Experiment group, select all the broad match keywords using a filter, and edit or replace them all to enable all those same keywords in BMM versions, adorned with the +plus +signs. My hypothesis here would be that the Experiment group, featuring BMM’s, would see a slight decline in conversion volume and revenues, with a significant improvement in ROI.

Recently, though, I got a different result. The “better” BMM’s resulted in a significant drop in conversions and revenue, and a slight worsening of ROI as well. In this complex, high volume campaign (and user behavior) universe, the broad match keywords that allowed the expanded matching were doing a significantly better job than the stricter match type. Evidently, the system was free to show our ads against more long-tail search queries and do so at reasonable CPC’s.

Expanded matching may still fail often, so this experiment could easily go in the other direction. The expanded matching may perform better, for example, when already buttressed by a robust file of negative keywords that you’ve built up over time. In that sense – when you’ve worked to augment it with your own manual exclusions – expanded matching may be “safer” in a mature, well-run account, and not so great when let loose without some supervision.

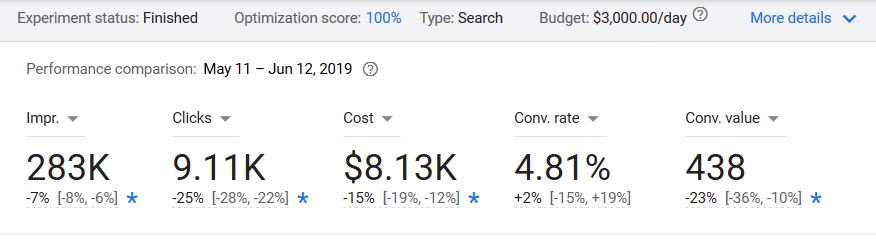

This Experiment to replace traditional broad match keywords with BMM failed, in our view, because overall clicks and revenue declined too much. Not shown here, Cost/Conv actually worsened (increased) by 11% — the opposite of what we expected.

5. Modifiers Matter Gambit

“What are you doing to optimize these campaigns again?,” challenges the skeptic. Some of the levers you mention – including very granular geo bid modifiers and dayparting in particular – are met with the objection “how much do these really matter? What’s the lift? Maybe 3%?”

It’s certainly a question worth asking, for a number reasons. Alternatives to optimizing these might include leaving all the modifiers at neutral (+ 0% bid), or allowing those modifiers to be addressed by a smart bot and not a human.

This experiment assumes you’ve been honing these modifiers regularly for a year or more and have a really nice file of accurate (you think) modifiers… or that you take a faster route and bid them all at once to take into account a long date range’s worth of ROI data – say, a year or 18 months. (The latter method won’t take seasonality and shifting trends into account, of course.) Keep your control group to the modifiers you created; set up the Experiment group to reset them all to zero. Compare aggregate performance as usual. If you prove the optimization was a waste of time – or that you weren’t able to spend enough time on it to result in better performance than not doing it at all – then by all means, deep-six the busy-work and leave them set to zero. Or rethink whether you’re executing well on your optimization, if that’s the route you’d like to continue to pursue.

Happy experimenting!

Read Part 10: This Hidden Trick in Campaign Experiments Will Blow Your Mind