Preamble:

Every few years, we go through a major turning point in the technology powering Google Ads creative. For example, our world changed quite a bit following the swift introduction of an array of ad extensions made available to enhance and adorn the basic text ads: Sitelinks, Seller Ratings, Callouts, and numerous others.

As I write this, we’re on the cusp of another major shift. It’s not just that some new features and testing methods are available, it’s the model of how we show the most relevant ad to each user that is undergoing a seismic shift.

The concept that online experiences are personalized is far from new. A community of UX (User Experience) professionals emerged back in 2000, with (among other venues) a website called personalization.com serving as the locus of discussion as to how best to tailor online experiences to individual users.

It’s been a long time coming.

But as we progress in the next year or two, our capabilities to serve “responsive” or “dynamic” content—particularly in ad creative—will be significantly heightened.

How? Largely—and maybe this is a bit scary to admit—through massive computing power. At the end of the day, each individual’s bundle of characteristics (ones that are salient to how they might respond to an ad, which in today’s realm can be measured) equates to a regression analysis: a statistical model of a recipient that can be matched to the closest possible equivalent among tens of thousands, or even millions, of precise ways of delivering a message.

(Think about attributes like screen size, browser, time spent on sites and apps, interests and passions, sophistication levels with technology products, themes of media passively enjoyed, explicit product comparison behavior, gender, income, location, and much more. In theory, humans don’t even have to know which characteristics to be on the lookout for. In theory, as we’ve been seeing from deep learning algorithms like DeepMind, AI could eventually be able to figure out certain tendencies or “rules” (ones we miss) simply by studying the patterns.)

All of this will be a far cry from the quaint, top-down practice of humans developing narratives and personas around the midcentury modern boardroom table in an ad agency, and then trying to hornswoggle a heterogeneous mass of prospects into buying into that persona. Narratives aren’t going away from the larger picture of advertising and persuasion. But for performance marketers, testing capabilities are about to improve exponentially. We’ll provide the raw materials from which we’ll discover the best ad for each user, as opposed to the “ad we show to most everyone that is the least bad in the aggregate.”

In light of that potential, what you’ll read in this part of the series will frustrate you. Indeed, contrary to good cheer and friendly trade propaganda going around about our wonderful testing capacity, our current testing capacity is merely good. It’s also rife with pitfalls and flaws. If you’re in a hurry to do a lot better, you may have moments where the realization dawns on you that our current approach to testing ads is actually crashingly bad when measured against near-term technological potential.

In recent years, while we’ve certainly enjoyed the ability to test ads and to be granular in who they show to, in a lot of ways, we’ve still been creating, testing, and managing to aggregate audiences.

New technology will help us with that user-specific customization. Specifically, it will be data-driven and eventually somewhere close to artificial intelligence. We’re not there today, but we’re getting closer.

Until we get there (partially, within two years—more fully, in ten), it’s as important as ever to understand a number of the basic principles that got us here, and to be able to execute on legacy, imperfect methodologies. There is a lot of money to be made each year in this journey that began in roughly 2002. That money doesn’t get made by sitting around waiting for the future to “just show up.” You’ve got to show up.

(For one thing, even in the amazing future, many campaigns won’t have high enough volumes for the machines to eventually learn on. You have to get good at this.)

Knowing what got us here, and executing in the current, imperfect environment—and then making the transition to more sophisticated approaches when they become available—will be the difference between you being compensated like an Uber driver and compensated like a top engineer at Audi (or who knows, maybe even running your own business and getting compensated even better than that based on how your business performs). Are you just along for the ride, or can you create the ride?

Read on.

Most advertisers know that you can run multiple ads in PPC platforms. Many dabble with simple tests, observing performance occasionally, turning off the losers, and so on. That’s a start. But let’s dig deeper.

Ad testing ranks right up there in the top three key elements of the Science of PPC. After all, the platforms are literally called Google Ads and Microsoft Advertising.

In theory, as account managers, we’re in control. It’s our job to maximize ad effectiveness.

It’s not an easy job. Way back in 2005, I published one of the first, if not the first, book chapters on this subject as it related specifically to Google. An example of a working theory: you will tend to find that “clever” or “creative” ads (of the type you might produce if you somehow tried to channel elaborate and costly Madison Avenue TV creative mojo into a tiny text ad) tend to flop. Then again, we shouldn’t be surprised. There’s little or no proof any of that is effective – you know, the taglines like “Go where your happy is.” Hey, if it floats your boat…

Upon reflection, traditional ad agency taglines are actually a way for the agency and the company involved to step aside from any value judgments. They aren’t persuasive, as the Mad Men era mythology would have it. They’re just getting in your face (often). A real tagline this year for a Hyundai SUV: “This is how you family.” Now you and I might both agree that this is drivel, but its genius is that it doesn’t say anything. (Also, thanks for the warning, Hyundai. I’ll do the opposite. But I digress.)

Another genre of traditional advertising seems to be the “ad agency in the death throes cry for help.” One ad currently running points to a (pain reliever) product’s efficiency and advanced technology, “just the same way we were able to squeeze this 30-second spot into 15 seconds.” Poor ad agency. Sad!

In the online realm, assuming we have conversion tracking installed, at least we can look at ad performance data to back up our testing hypotheses. Drawing appropriate conclusions from the data isn’t an easy job, either.

Above all, get started

Don your lab coat. Roll up your sleeves.

This represents an opportunity. If your competitors are neglecting or outright bungling a key building block of account management, you’ll be more profitable than them with each and every impression and click. The cumulative effect can powerful.

Winning ads rarely fall into place just by grasping the basics or by tacking on a few new shiny formats. You need to have a solid grasp of PPC ad testing fundamentals, a trove of creative inputs, tailored insight into the company’s product(s) or service(s), and curiosity about the psychological triggers that may lead prospects to respond differently to different ad elements. Is it:

- Price?

- Quality?

- Unique positioning?

- Timeliness?

- Whim (as in, what the hell, McFlurry today?)

- Weather? (It’s hot, cold, snowy, perfect, etc.)

- A promotion?

- Joy?

- Adventure?

- Vanity?

- Love/family?

- Fear?

- Green and natural or socially responsible?

- Simply healthy (organic, non-GMO, etc.)?

- Fun?

- Memories?

- Ego?

- The seller’s reputation?

- Location?

- Features?

- Does any of that matter, or does a firm and decisive description of the product, service, or product line matter the most?

Google Ad Rotation 101 — Already Reaching for the Anti-Migraine Meds?

Let’s cover some basics of how Google Ads testing works (for text ads) before moving onto some of the complexities.

Feel free to skip this if it’s old hat to you.

The fundamental building block of a Google Ads account – the ad group – is made up of a handful of (or one, or many) keywords centered around a certain theme, such as a specific product or product line (Organic Budgie Food, for example). You may rotate multiple ad versions against that set of keywords, which in themselves map to a narrow or wide universe of potential search queries.

So it’s actually misleading to suggest that an ad is “better” or “the” winner. Every time you do this, you’re actually counting aggregate results across a lot of different kinds of user experience; different queries; different user intents; and so on. Some ads might perform better for slow readers. Some ads might perform better on phones, and worse on larger screens. We soldier on anyway, making more profit if we’re willing to find the messaging that travels well across enough of these boundaries that we can make sense of the aggregate results. (Granted, this is imperfect, but that’s bloody well how it works. Until the future arrives. Remember what I said above about trying to find the ad that is least bad to a relatively large group of people? Even if campaign structures allow for granularity, that shouldn’t be confused with advanced personalization.)

On any given search query, the ad system will serve one of your ads in one of the designated ad slots above or below the organic search results on the SERP (search engine results page). Your ad isn’t guaranteed to show up, though. Quality Score determines both your ad position and eligibility in the auction on each and every search query that theoretically overlaps with keywords you’re bidding on. Keywords (and ads – keywords and ads are in a sense inseparable) accrue Quality Scores over time. Google uses the accrued information, but doesn’t map out exactly how. There is no hard-and-fast number of days that must pass, or number of impressions that have to be racked up, before Google increases its confidence level in the quality of a new ad or keyword (or user responses to your website). We do know, though, that new ads and keywords generally are, in some sense, on trial. Your new campaigns will take time to gain traction.

Multiplying your keyword’s Quality Score by your Max CPC bid results in something called Ad Rank. Google nearly instantaneously compares the Ad Ranks of all eligible ads in a given keyword auction, and serves ads on the search engine results page (SERP) accordingly. (“The” SERP is itself a misnomer. Users will see many different layouts and rankings, not least depending on what type of device they’re using.)

Keyword Quality Score: Three Components

As onetime Google AdWords Quality Score czar Nick Fox once mentioned to me, most elements of the Quality Score formula “come back to being another take on CTR.” While not revealing weightings, Google now publishes indicators for three “components” of Quality Score. You can modify columns when viewing at the Keyword level to include these various additional pieces of Quality Score information. The three components are:

- Expected CTR

- Ad Relevance

- Landing Page Experience

All of these terms may be shorthand for a whole range of underlying computations. For example, Landing Page Experience has often been referred to by Google under the aegis of Landing Page and Website Quality. This latter bundle includes a range of policies against bad user experiences like intrusive pop-ups, failure to disclose physical address information, and so on. (Yes, Google hides policies, which might sometimes be enforced by humans, inside a numerical “score.” You can call this disingenuous or you can simply refer to it as “Googly.”)

So why are we talking about keywords when we’re talking about ads? Well, your ads (in concert with your keywords) generate the outcomes that directly impact two components of Quality Score: CTR and “ad relevance.” If your ad isn’t clicked on very often, you’ll probably need to experiment until you find ads that have a better CTR – since poor CTR will lower your keyword Quality Scores. Ad relevance is murky, but you can get a take on it by simply looking at examples of Quality Score components as reported by Google Ads. Take this example:

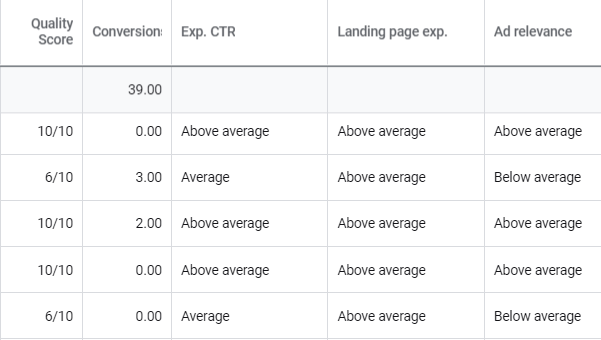

Figure 1: Quality Score components being reported at the keyword level.

The components sync up intuitively with the numerical Quality Score. The “10” scores above average on every component, whereas the “6” has an average CTR and Google has deemed the ad not to be relevant enough.

What’s going on here? Well, I can reveal that these particular ads are for a full line of bags and purses, and the landing page shows a wide selection of them. Keywords that refer to backpacks, bags, or just the brand name, fare quite well Quality-Score-wise, apparently because they’re in sync with the verbiage in the ads. This might be considered a best practice insofar as “see keyword, click ad, see what you expect to see” – a phenomenon long known as “information scent,” as coined by Jared Spool et al. of Xerox PARC labs.

If the disconnect is great enough between the ad (or other linked material) and what the user finds when they arrive on the landing page, it may even trigger the phenomenon known as “I came, I puked, I left.” (With thanks to Analytics expert Avinash Kaushik for this fanciful definition of a website “bounce.”)

In most cases, Google’s Quality Score computation is surfacing a relatively minor disconnect, so it can be annoying.

In the case pictured above (Fig. 1), when we advertise on the keyword “totes,” or “wallet,” but fail to include that word in any of our headlines or ad descriptions, it’s predicted that users may have trouble seeing the point of the ad. More often than not, though, this is a false alarm. Users still hope to find totes when they’ve typed totes yet only see general references to bags, so they carry on and (in this case) find and purchase the totes at the same or better rate than any other consumer typing queries that trigger these ads. In fact, the ROAS (return on ad spend) for the totes keyword is more than 4X the adgroup average, albeit on low volume.

So, let’s ignore some of the noise and focus on the keys to success.

CTR is one main differentiator among ads, and you’re rewarded for that. But your business doesn’t run on clicks, it runs on revenues. Two KPI’s that may often run at cross-purposes: now what?

Plan your KPI’s

Sadly, some of the advice you’ll commonly read in the industry still refers only to clickthrough rates. That leads to a kind of surface level quality to the advice. You’re supposed to “drum up enthusiasm” for your ad. That sounds “creative,” but it isn’t scientific and it isn’t, well, business.

Each business is different, so criteria for what counts as a winner should vary depending on your business model.

Your ads, not everybody else’s

Not by accident, I’m emphasizing poking the box—direct experimentation—rather than sitting back and digesting reports about broad principles that work for a large sample of advertisers. Success is spawned, ultimately, in the nooks and crannies of each specific ad test in each specific ad group.

There are some consistent principles that are important to grasp, even if you sometimes go off on your own mad chase. By observing ads in the wild, you’ll likely come to perceive these trends sooner or later.

Key principles include:

- Headlines matter most.

- Customization and granularity for the win! Refer directly to the product or service the user searched for; don’t bother advertising on keywords that are too unrelated to that.

- Do the Display URL and/or Destination URL form part of your ad strategy? You bet. The Display URL is typically a company name. If you’ve got a strong brand in the first place, you’re ahead of the game. Sometimes, an inability to break through in the all-important PPC auction will prompt a rebrand or a new domain name and spark success. Your mileage may vary.

- As for the destination URL, it’s not always obvious what landing page will lead to the best ROI on advertising. Sometimes, it’s a matter of landing pages needing improvement. What is the appropriate level of granularity – a category or a product? You’ll want to test. And some companies and their users defy logic. We have a client (with many products) that simply makes more money if we send everyone to the home page. (Don’t judge.)

- Shipping offers, benefits, time-limited offers, positioning statements (geographic or otherwise), granular descriptions of products and their ingredients… every situation begs for testing factors like these, and many others. Some of the core drivers will become settled early on (let’s say a strong regional presence – you’re “Oregon’s Choice for Oregano”).

- Testing small variations can matter in large accounts, but don’t get caught up in minutiae. If three of your ads are pretty similar, make the fourth depart significantly from the trend. For example, for a niche kitchen brand with multiple categories, list a few of the specific items (pepper grinders, graters, meat thermometers, and spatulas). If that type of ad has a chance to win, why not mix up which items are included in the list, and their order? We’ve seen winning ads come out of a test like this for reasons that can be best explained by “certain words bounce off people’s eyes in a way that makes you more money.” ☺

- Be wary of unwittingly excluding people. It’s a common statistical fallacy to assume that a highly specific persona is what we should be going after in advertising. Dead simple example: if you’re sending visitors to a category page with rakes, shovels, hoes, and garden gnomes, you may find that the ad referring only to the shovels (because the brand is an iconic manufacturer of shovels, primarily) underperforms.

- A more striking example of stereotyping might be to recognize that men purchase certain types of makeup. Sometimes, they might be buying it as a gift or as a favor to a female friend or significant other. Other times, they might be buying it for themselves. The same principle applies to the age of the purchaser. Sticking to the makeup example, sometimes people who are “too old” or “too young” to buy certain products (as stereotyped or profiled by the creators and distributors, or even society / peers), well, buy them anyway. (Again, sometimes for a gift, and other times for themselves.) The effect might even be magnified online, since the buyer doesn’t need to go into the store and deal with judgments about not being in the target market for the product. Any ad verbiage or bidding strategy that gets hyper-specific to a demographic could exclude up to 25-30% of one’s potential sales, in this example.

- At the SERP (search engine results page) level, users’ brains are at the navigation and “sorting” stage, and only mildly susceptible to persuasion. Folks are often scanning quickly. They’re not generally “listening” to flowery verbiage, unless this happens to be a wacky part of your brand identity.

- Simple words beat complex words, with some exceptions. Many B2B advertisers use acronyms and jargon, but these puzzle a scanning brain even when that brain is owned by a highly educated professional. (Prove it to yourself – test!) Such rules are made to be broken, of course. In one ad describing a manufacturing process, I tried the word “meticulous” against a simpler word: quality. Meticulous won by a fair margin. Four whole syllables! The lesson there is that higher-end products may have their own rules. Higher profit margins may demand that you depart from clichés. Then again, “quality” is working in other parts of the account. In some fields, quality manufacturing is rare – not a cliché!

- As you’re starting out, give all the clichés you can think of a fair spin of the wheel. All this costs you is some brain work and post-facto analysis. Referring to “speed” and “fast,” for example, sounds like it wouldn’t move any needles. But have you heard any consumer wanting slow shipping or homeowner that prefers a slow response from a roofing company?

- Try being specific. To take the speed example, if you can guarantee three roofing quotes inside of six hours, say so.

- A decade ago, I decided we would try “Super Fast Shipping” as a benefit in ads for a company that sells snacks. That verbiage only worked for… oh, about ten years. So have a little fun while you’re at it.

- The beauty of reviewing your unique selling propositions (USP’s) is precisely that it avoids “excessive promising” that causes a click followed by disappointment (that’s costly!). (See Jakob Nielsen, “Deceivingly Strong Information Scent Costs Sales.”) If you offer a slightly more expensive training course that offers the hands-on, in-classroom touch, be sure to highlight that benefit – both to emphasize your strengths, and to discourage people seeking very inexpensive online courses from clicking on your ad.

Calls to action

Of course, you must test calls to action (CTA’s).

Test two or three. Test with or without. Keep re-testing periodically.

In technical or long sales cycle fields where “buy” or “shop” is not the call to action, you can make significant progress in your PPC campaign’s economics just by tinkering with the various ways to say “free trial”, “no obligation”, “request quote”, “download”, “order a sample”, and so on.

The world is full of amazing business owners who have figured out how to massage prospects into an upscale purchase. I’m grateful to have learned from so many of them.

One old trick – and I can only imagine it doesn’t work as well today in many industries as it once did – is to put something weighty in the prospect’s hands via postal mail. When you’re thinking something over, it’s nice (for the seller, especially!) that you have a kit that’s been diabolically designed and perfected to keep you thinking it over.

Long ago, we had the distinct pleasure of working with Dick Mills, a retired MLB pitcher who had snapped up the domain name Pitching.com. He ran a training camp for young pitchers. (He died in 2015, but the website and the courses are still in business.) The “help you decide whether to enroll in my camp” kit worked like a charm. The return on the online advertising investment was strong. And of course we tailored our calls to action to the specific action we wanted the prospect to take first, so that they would start to seriously think it over.

CTA tests can yield powerful results indeed.

Calls to action that don’t relate to your primary conversion goals, by contrast, can be worse than neutral in their effect. Unless you’re very sure that you want every visitor to go into “research mode” when they *might* well have purchased, requested a demo, or picked up the phone and called, you’ll no doubt learn to avoid too much talk about learning and reading (sorry, bookworms).

Translating some of the above principles into some of your own ad tests will be a challenge, but by no means is it terribly onerous. So have fun!

How much research?

In the old ad world, when very large budgets were at stake, a “research department” was seen as a must. Larger companies typically engage in considerable consumer research (on attitudes, needs, impressions of a new type of cookie or golf ball, etc.). You shouldn’t worry if you don’t have a research budget or a person who is a “consumer research expert.” We’ll cover competitive intelligence and benchmarking in a later part of the series. But many good campaigns have been launched with only internal meetings at first. Real customers and skeptical prospects will be visiting your site and doing business with you (or complaining, or not doing business with you). Research them.

mDNA

Diversity and serendipity in idea-seeking seem to result in stronger companies. Seth Godin calls this mDNA (for “meme DNA”). Even in the process of coming up with out-of-left-field thoughts for ad elements, it can be useful to grasp this aspect of natural selection. Every so often, a winning “mutation” appears, strengthening the organism’s chances of survival (or even helping it thrive).

So don’t hesitate to ask a junior person or a layperson how they would word a product benefit or any ad element at all. Toss it into the mix.

Sometimes we’ll run an ad contest. Internally at Page Zero, we mini-crowdsource the ad creation process just to see if any of the new ideas will shake things up. And I’m not here to preach, but it helps if you practice diversity in your hiring practices. Being willing to give everyone a voice is as important as who you hire.

Although natural selection is the quintessential scientific principle in the natural world, of course this definitely gives us a glimpse of where individuals can unleash their creativity in this process. Art and science, beautifully melded. Maybe that’s all we are – bundles of potentially beautiful and talented cells striving for survival in a deadly contest. And so goes your ad account.

To be scientific in advertising, do you need to be a scientist?

No! You simply need to understand the methodology. But it also helps to have a deeply inquiring mind about probability and statistics. Some classic texts (some became instant classics) to the rescue!

One of our favorites is David J. Hand, The Improbability Principle. You should also check out Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Fooled by Randomness, and John Allen Paulos, Innumeracy.

Behavioral economists like Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, by the way, have pointed out that we humans are “poor intuitive statisticians.” Studies have shown that rapid-fire guesstimates of statistical significance provided by professional statisticians with PhD’s betray the fact that even these experts have poor intuitive judgment of what we can confidently assume from a dataset. As a start, check out Daniel Kahneman, Thinking: Fast and Slow.

Long story short: don’t trust your gut feel. Don’t pull a narrative out of your… out of thin air. Many experiments in all disciplines return inconclusive results, though it isn’t sexy to say so.

Without any further ado: you can easily measure how likely an apparently winning ad version is to be the actual winner (based on your chosen KPI – let’s say it’s Conversion Rate), and not simply due to statistical randomness (chance).

Use a calculator!

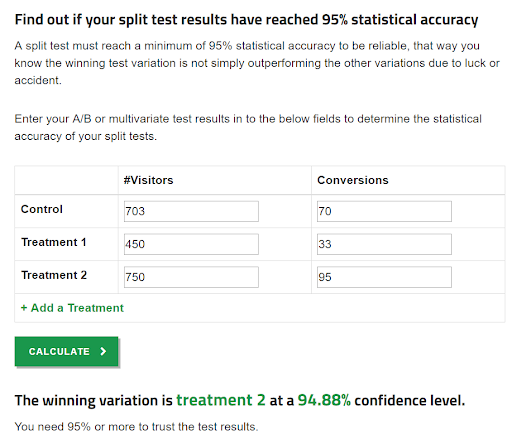

Try tools such as the available (free) statistical confidence calculators from House of Kaizen.

Figure 2: 94.88%. Close enough.

You’ll notice many of these calculators are geared for A/B tests of (let’s say) landing pages as opposed to ads. Or they measure the winner by CTR, as opposed to, say, CPA or ROAS. The same basic principles apply.

Dedicated ad testing tools like AdAlysis and features within tool suites like Optmyzr allow you to perform more dedicated and custom analysis, and may be suitable for some advertisers.

The biggest error people make in the ad testing process is to end tests too soon.

Time and again, you’ll find that big gaps in performance tend to regress to the mean. (If that doesn’t happen, great! Winner, winner, chicken dinner!)

On the subject of patience: you’re well advised to let your testing data “settle.” Assess data after 30, 60, or even more days after the time frame under consideration. (For small datasets, though, you might need to assess tests over 6-12 months.)

The importance of “settled data” can be chalked up to the fact that attribution in our field is now quite good. Many times, purchases come along in latent fashion, after consumers finally make up their minds on a purchase. And oftentimes, yes, those delayed purchases are eventually attributed back to one of the ads in rotation. You can get a sense of the time lag to purchase via the aptly named Time Lag to Purchase report (under Multi-Channel Funnels) in Google Analytics. For a typical client of ours, only around 50% of attributed online revenue occurs within one day of the first known interaction. The other 50% is spread out over 45 days (and to a much lesser extent, even longer than that). It’s probably more like 70%, but apparently even Google Analytics isn’t omniscient. We’ll dig into this more down the road.

A more subtle mistake in picking winners is to applaud an ad for high ROAS (Return on Ad Spend) based on one or two high-ticket orders (definitely could be correlation without causation), even though the conversion rate on the ad was about the same or even worse than other competing ads. If an ad really causes larger orders, it’s going to need to prove that over a large pool of data.

There is a lot of random noise in any data set; this is certainly so in ad creative testing. Don’t confuse luck with causation.

Oh no! Everything is inconclusive! Now what?

One of the primary causes of inconclusive ad tests can be chalked up to enthusiasm. Clients want to see more effort. (We once had a client who yelled, in a perfect southern accent, “I wanna see some dust fly!”) Practitioners want to contribute to that effort. But to see meaningful wins from a test, we’re (typically) going to want to see at least two ads running against each other with several hundred clicks apiece, if not more. Heck, I’ll take over 1,000 clicks each if I can get it.

You can’t blame anything on an ad that has just 50 clicks. Maybe it hasn’t converted yet. But you say the test has been running three months? Great. You’re looking at another 6-9 months before you’ll have statistical confidence, in many cases.

It also depends on the attribution model you’re using (to assign conversion credit to clicks in situations where the same user clicked on and/or viewed various paid and unpaid messages over time). Of course, I’ll discuss that in a future part of this series.

On low volumes, then, consider running just two ads; three, tops.

Because accounts tend to be pretty granular, we’re often working with low volumes for ad tests. Advertisers with more high-volume keywords and ad groups are in the fortunate position of being able to learn more from testing sooner. But to be clear: most of you won’t be in that position most of the time.

Contaminated lab?

If you’re a fan of easy solutions and an air of certainty (i.e. not science), feel free to skip this section.

Unfortunately, our experimental environment isn’t pure and controlled. One ad may not be literally pitted against another ad under “fair” conditions, given how different the environment may be (ad position, device, Google subtly testing different SERP layouts, and more) for each user. Certainly, with larger datasets, the ad creative may prove decisive regardless of potential contaminants, as they should even out.

But how causal is your ad, really, given that the presence or absence of ad extensions is also a factor in influencing users? Although you participate in setting up your ad extensions, ultimately Google’s machines control the constantly-shifting display of adornments like Sitelinks extensions, seller ratings extensions, and call extensions. Google’s systems learn in part by being inconsistent: by feeding unusual combinations out into the marketplace sometimes in order to collect data on how users react to everything. This learning may be useful, but it also plays havoc with your testing lab. Be wary of any advice on ad testing that seems unaware of how uncertain the process may be.

It’s easy to lose sight of the presence of uncertainty – the Google Ads interface lulls you into thinking your tests are pure, and that the creative you add is going to be rotated systematically in a way that you can directly observe.

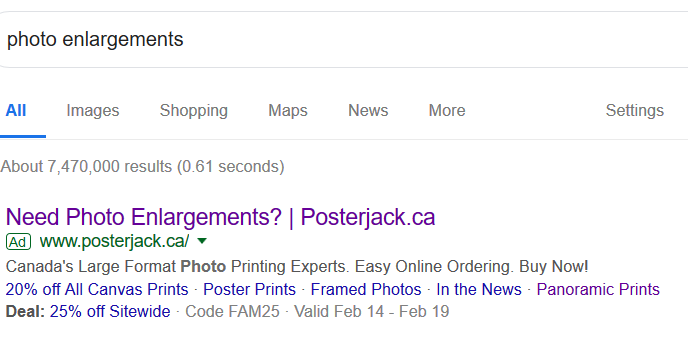

Figure 3: Simple, yet effective, ad. The description copy probably doesn’t carry huge causal weight.

So while we might be tempted to measure elements of ad copy effectiveness across different campaigns (“If I can maaake it there, I’ll make it… anywhere!”) we need to ask hard questions. What if – completely out of your control – Google was showing your Seller Ratings Extension more often in one campaign, but not in another (due to competition, your bidding, your different Quality Scores in different parts of the account)? This might affect how often your ad shows up or gets clicked in one or the other campaign, among other things.

Another complicating factor is multiple campaign types. For Client P, we might have shown up in the Google Ads auction one of three or four ways. In short, one campaign can “cannibalize” queries away from another. Emphasis shifting around from one campaign to another, unpredictably? That doesn’t sound like ideal laboratory conditions.

Ultimately, we can’t put too much stock in small datasets. But we may not be wise in aggregating datasets from dissimilar situations, either.

Take the obvious wins. Always beware of simple answers and claims of enormous lifts in performance from ad testing. Unless your baseline is horrible, wins from ad testing should be incremental, not mind-blowing. A lot of incremental improvement does add up over time. But be realistic.

And there’s more! Third headlines and second descriptions

Another wrinkle in testing nowadays is greatly expanded ad formats. Google hasn’t always allowed the addition of a third headline, let alone a second, in the ad creation process. Also new is something called a second description. The ad serving system might show the additional text sometimes, but how often is really anyone’s guess. You might even want to try a “with and without” test when it comes to second descriptions, for example.

All by way of saying: if you casually drive by a PDF or spreadsheet of someone else’s ad test results, don’t hang too much on the apparently gargantuan amount of description text. It’s quite possible the additional verbiage is rarely shown.

More to the point, though: what to do about this capability? I’d place it somewhere below medium priority, but it certainly isn’t low priority.

First off, your existing ads probably aren’t great yet. They may be good. So work on improving them.

By all means try additional headlines and descriptions every so often. In most accounts, it’ll take some time before you know if they’re paying off.

Don’t do this busywork only because someone thinks you’re lazy if you don’t.

This is about performance: the financial kind. It shouldn’t be the theatrical kind.

A seed of doubt? Don’t plant one.

Since inception, for skilled advertisers, PPC keyword search ads have generally returned high and measurable ROI. No small role has been played by the degree of trust consumers place in these ads. They don’t come off as corporate, cutesy, or self-serving. They’re matter-of-fact; helpful.

Sometimes we may violate that trust with hyped-up claims. But it may only take the planting of a small seed of doubt in the consumer’s mind to contribute to shocking divergences in the performance of two different pieces of ad creative.

Case in point: one client needed to hedge on a certain issue to ensure that no consumers got angry with them around some subtleties in their offer. And they decided that in addition to placing clarifications and disclaimers on their website, they’d do so in their text ads as well. And that hedging came in the form of… drum roll… an asterisk*!

Apparently, consumers dislike asterisks.

As it turns out, it was only there to appease a tiny subset of complainers. People who hold corporations to a standard of 100% perfection. Less than 1% of prospective customers, who would turn out to be good customers only 0.1% of the time. And yet everyone got to see the asterisk.

Of course, if you’re showing prescription pharmaceutical ads on TV, you may have to provide warnings of side effects that might not affect 99.5% of patients. There’s nothing you can do to get around that. But in our field, as Jeffrey Hayzlett has pointed out, if you’re a little less than perfect in an ad campaign, “no one dies.” We are terribly important people, we marketers, but it isn’t open-heart surgery.

So how did “ol’ asterisk” do?

Across all ads in a rather large account, the performance gap was stunning. A significantly lower CTR. Greatly different conversion rates and ROAS (23.3% lower ROAS – goodbye profit!) from these “asterisk ads.” I wouldn’t have believed it possible. But the data spoke.

The principle of “don’t cast a seed of doubt” might well be lurking as the root cause of a lot of your puzzling ad underperformance. Think about it when troubleshooting.

Don’t make me think, unless I like to think

Although I’ve referred to this principle at least twice already, I’m not above beating a dead horse if it helps the message get through.

Steve Krug wrote a famous book on landing pages and website navigation: Don’t Make Me Think. If that principle applies to websites, why not see if it affects response to your ad copy?

- Version 1: “No additives, parabens, or GMO’s.”

- Version 2: “All-Natural Ingredients.”

Which one won? Here’s where it gets a little painful.

Oftentimes, one ad wins for CTR and the other wins for conversion rate. They’ll also often come with different typical order sizes, and like I mentioned, it can take a long time before you can conclude that the ad had any causal weight in order size.

In this case, despite a reasonably long testing period of several months, neither version is gaining the upper hand.

Here’s what I think may be going on. The simpler ad is better for the average person. But as Avinash Kaushik once pointed out, not a single person visiting your website has the given name “Aggregate.”

The ad mentioning buzzwords is going to captivate a serious “insider” type of buyer in some cases. Ideally, we would show just the right ad to just the right person, but that’s harder than it looks.

With a smart campaign structure, use of demographic bid adjustments at the adgroup level, and also adjusting Audience bids (such as In-Market, or newly-available Audiences called Detailed Demographics), we might start to see some more decisive patterns emerge, such as a non-GMO reference actually beginning to win more consistently.

I say might.

At least I’m asking the hard questions, and proposing potential optimizations. The average campaign manager (as opposed to the “serious insider type” of campaign manager) has no idea all of this is even going on under the hood. In the PPC game, overconfidence kills.

Anyway, to recap: the standard For Dummies narrative would probably tell you that “all natural” was obviously better because more people could relate to it. But that seems to assume all consumers are dummies, when in fact many niche consumers are increasingly educated. So the subtle and important point to make about those two ways of expressing the same thing is that one way appeals to some people, and another way might appeal to other people.

And yes, as stated in the preamble, with nearly 100% certainty, as something approaching artificial intelligence emerges down the road, ads will be able to speak in the vernacular of their target audience not because an account manager chose a segment and got really granular with the strategy, but rather because software, drawing on a menu of possible messages supplied by the advertiser, will adjust the message ever more subtly to the style that results in better response. That day isn’t here. Nonetheless, you can still think about what appeals to your best and most numerous customers, and do better today than you did yesterday.

Pick a winner, or have Google choose for you?

In the early days, the process of managing ad tests used to be entirely manual. Today, you can automate it in various ways, but many pros like to be quite hands-on in the initial crafting of ads.

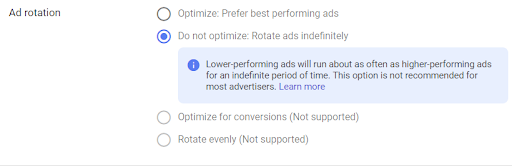

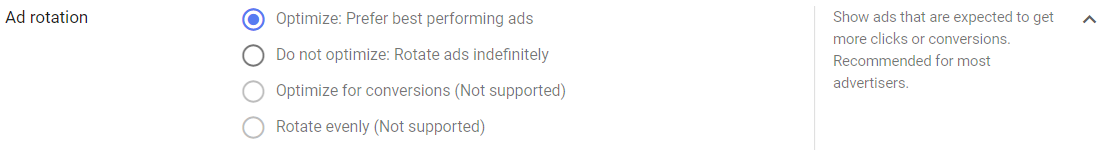

In Campaign Settings, ad rotation is set to one of:

- Optimize: Prefer Best Performing Ads

- Do Not Optimize: Rotate Indefinitely

There are also some legacy “non-supported” options that have lingered in the interface (with the caveat that they don’t work) for whatever reason. This includes “Optimize for Conversions.”

Figure 4: Sigh. Advertisers have long been dissatisfied with Google’s misleading settings for ad rotation.

As of this writing, “Prefer Best Performing Ads” is defined as “Show ads that are expected to get more clicks or conversions. Recommended for most advertisers.” Seriously? Shouldn’t this be against the law? Which is it? Clicks or conversions? Google will decide. It’ll likely be more clicks.

Figure 5: Took a screenshot, so no one can accuse me of hallucinating.

In theory, we still have some control over our own ad tests with “Rotate Indefinitely”. The rotation isn’t even by any means (Google stopped promising that forever ago), but if we’re patient, there’s a solid chance we can carry out a reasonable testing agenda.

Now, as the screen shot below indicates, you can set ad rotation at the ad group level whenever you wish. (Formerly, this was only settable at the campaign level.) This might be useful in cases where you feel like you want to run your own tests on part of the campaign, while ensuring that the automation is picking good (albeit likely favoring CTR) ads to serve on the parts of the campaign you aren’t going to be able to stay on top of.

Do ad extensions help? How much?

Ad extensions come in an increasing variety of formats. In every case, Google’s algorithms decide how often, whether, and which ad extensions to show along with your ad headline(s) and description(s). Here are a few of the main ones:

- Sitelinks. This is probably the best known, because they resemble the “sub-navigational” links that also sometimes appear below high-ranking organic search results. Enhanced Sitelinks show a description line as well.

- Callouts. Basically it’s to your discretion whether to highlight an additional benefit (Open 24 hrs.; Over 100,000 Listings; and so on) on top of whatever you cram into the ad description.

- Seller Ratings. If you’re using an approved consumer review service, Google aggregates the star ratings into a nice visual (orange) “stars” graphic. Eye-catching.

- Structured Snippets. A fairly open-ended means of showing more information about your offerings. For example, an accommodations company shows “Types: Hotels, Apartments, Villas, Hostels, Resorts.”

- Deal: For special offers.

There are numerous others.

Google does show the stats associated with your extensions. Be aware that the associated metrics show what happens when that particular extension or aggregated stats for that class of extension shows with your ad. Don’t assume these extension stats imply causation; it isn’t “clicks on extensions” that results in those metrics (Sitelinks is the only type of extension you can click, anyway; users rarely do).

Extensions have a couple of obvious benefits, and possibly some less obvious ones. The most obvious benefit is that they improve a top advertiser’s ability to dominate screen real estate as against other advertisers, and for all advertisers’ ability to dominate screen real estate in comparison with organic search results.

Not infrequently, ads accompanied by certain ad extensions underperform ads with no extensions at all. Some extensions nearly always perform worse than others. You’ll be able to see that in your stats.

But surprisingly, we do see some significant differences in results if we test enough variations on our extensions. Unfortunately though, that may not suggest that we’re boosting our ROI by trying out all kinds of extensions; rather, we’re sorting out which extensions seem to be at least neutral in their impact. It’s a good idea to collect lots of data, and also a very good idea to remove the extensions that are underperforming.

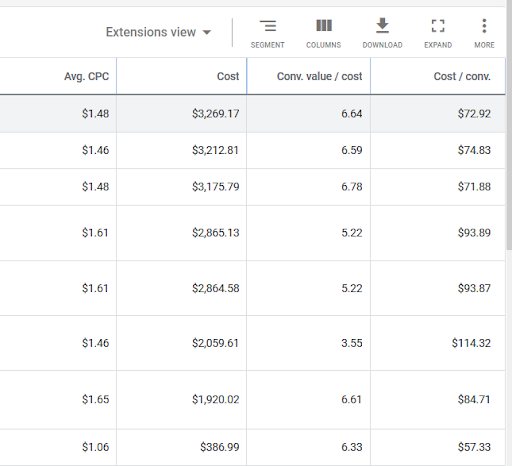

I’m not a fan of how Google reports on extension performance, but perhaps it’s inevitable given the complexity of all the options.

If you’re able to figure out how to get there, (Ads & Extensions > Extensions), you’ll have the option to view “Associations View” or “Extensions View.” Below, I’m viewing Extensions View. I’m horrified to note that some of our Sitelinks extensions result in significantly worse ad performance. Weird! But typically, we’re superstitious enough about screen real estate (and CTR), especially in mobile, that we are (probably rightly) afraid to do without extensions. Anyway, in this case I’d consider eliminating the Sitelinks extensions that appear to do harm (especially if you can work out why they’re harmful, such as having distracting information that causes the prospect to freeze up and lose what Bryan Eisenberg has called “persuasive momentum”). Try a longer date range and a larger data sample before you make any decisions. Anomalies in performance tend to even out over time.

Note also that the top three lines show data for the three Callout Extensions. They don’t appear to harm performance, but within their extension type, none appears to win. They’re all performing about the same. It is perhaps for this reason that I equate the whole Extensions game with a kind of window dressing – partly tongue-in-cheek, understand. See “Why I Hate Ad Extensions.”

Figure 6: I hate how Google Ads reports on Extensions, but FWIW, here is an example (with client data kept private).

“At least neutral in their impact” sounds pretty lame. But because screen real estate is so important, especially in mobile, you need to dominate that real estate if you can afford to. You might find that hurts a bit financially. Welcome to Google’s wonderful world of diabolical revenue maximization. They’ve figured out complex ways to make more advertisers feel better about chasing the top couple of ad slots.

There’s one more reason why you shouldn’t get too ambitious, or put too much stock in, extensions. (And why you need to go back and check performance.) At least when it comes to Sitelinks, link rot can set in. So you either get disapprovals when site architecture changes and the destination URL goes away, or you keep cruising along with an outdated page. A year or two could fly by without you noticing this, so pay attention!

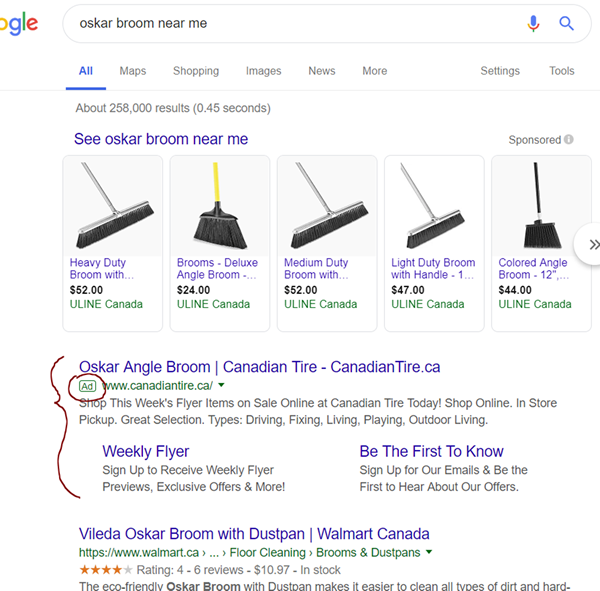

Figure 7: Screen real estate is super-important. Canadian Tire and Walmart Canada know it (though apparently they’ve forgotten to optimize their Shopping campaigns).

When does ad testing matter the most?

Finding winning ad creative always matters. But for sure, there are times when it seems to matter more. A couple of examples:

- A high-volume product line such as a mainstream small-business (SaaS) product that relies heavily on a narrow set of keywords. You’ve got all the volume you need to test a whole range of potential benefits, ways of positioning the product, calls to action, etc. There isn’t a need for endless customization and segmentation. The way you express your offer may have a huge impact on your cost per acquisition, both by weeding out non-prospects and by putting prospects in the right frame of mind.

- A very high-volume e-commerce site with many products and categories, but with similarities in how the consumer thinks across them. With massive volumes available, even small variations in wording may have a big impact. Even larger impacts will come from settling on key triggers, calls to action, and major elements such as the second headline.

- A lower-volume retail business that relies heavily on just a few products, in which the consumer is crying out for some means of sorting out which of several companies has the highest quality or is the best fit for them. Moreover, the items are high-ticket, emotional, and have a moderately long sales cycle. The testing process may take longer here, but the profitability difference between bad, indifferent, good, and great ad versions may be decisive.

SERP takeover: ads, ads, ads

Text ads take up more space than they used to. To somewhat compensate for that, Google reduced clutter by cutting down the number of advertisers that really have any shot at showing up in any given auction (crappy, spammy ads are much less prevalent than they were 8-10 years ago). And ads were removed from the “right rail,” making it a better user experience, especially on mobile. But make no mistake, the user is seeing a lot of ads. Sometimes only ads.

Generally speaking, bigger text ad units have been a win for advertisers. This is partly because impression share (and thus clicks) has risen for the paying advertisers; there has been a corresponding drop in organic search volume. This is particularly dramatic on mobile devices. Obviously, more exposure can be an expensive proposition for marginal ad messages and poorly-run companies. The current Google era of Max Ad isn’t friendly to weaker companies and less optimized accounts.

Advanced ways of testing ads

Above, I mentioned some examples of high-volume PPC advertisers.

For some such clients, after testing major drivers for a couple of years, we experimented with forms of high-volume, brute-force testing to see if we couldn’t come up with additional small refinements. In addition to that motivation, we knew from the world of landing page optimization that sometimes it’s a rare combination of elements that just seems to gel perfectly for the average prospective customer. You only get to discover such combinations by setting up a testing methodology that can uncover a winning permutation based on a structured plan. Long story short, this is called multivariate testing.

There are tools you can play with to accomplish this, though they’re hard to find. We implemented partial factorial testing using the Taguchi method. In some tests, just one or two ad variants among hundreds or thousands came away big winners. There are quite a few controversies in this field, but the results of the process were evident to us and profitable for our clients.

Hopefully we’ll see such tools evolve and become more user-friendly in contexts like Display advertising and Facebook advertising. As of this writing, many in the industry are referring to the term multivariate testing (for Facebook ads, for example) without actually doing multivariate testing. I guess it’s clickbait.

In 2018, Google rolled out a multivariate ad testing feature in Google Ads called Responsive Ads (somewhat misleading name, but powerful functionality and great potential going forward). Unfortunately, as with many Google products, Responsive Ads lacks transparency, doesn’t predictably serve all or even very many ad combinations, and provides sketchy reporting.

That being said, the tool is beginning to shine as it evolves. It’s become easier for the average person to use. And the decision Google has made to (non-transparently) choke off impressions for combinations that aren’t predicted to perform well (even very early on, favoring predictive approaches over retrospective “proof”) may well be appropriate to the task at hand, greatly reducing the time it takes to find and favor winning combinations.

The interface even prompts you to create more meaningful tests. It’s early days yet, but Responsive Ads and similar technologies appear to have a bright future. It’ll be up to you to fully tap that potential.

I’ll cover Responsive Ads and similar features in more depth down the road.

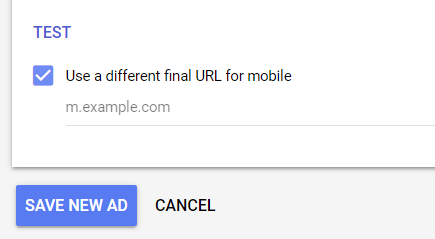

You can split traffic for mobile-friendly landing pages

You might be interested to know that Google Ads has a handy feature to help you out if you have put in some work to develop a mobile-specific landing page. When you’re setting up your ads, you’ll have to split traffic so that mobile users go to the mobile-friendly page, and everyone else goes to the original.

We no longer have to handle this customization via campaign structure (recall that in the good old days, we had to create a duplicate campaigns broken down by device type). We also don’t have to arbitrarily favor one version of the page for PPC (for example, by determining that 70% of users in a campaign are using phones, so making everyone go to the new phone-friendly page we’re testing). Google has added an easy setting in the ad setup process that allows you to opt for a “different final URL for mobile.”

Figure 8: Don’t shy away from tailored mobile landing pages. Ad destinations are easily handled with this setting.

Walk this way: encouraging larger orders

In retail, let alone business services, it’s pretty hard to dictate to someone how much to buy. That being said, we know how important that is to retailers’ profits. Grocery stores, liquor stores, toy stores – and who knows, maybe even car dealerships and new condo showrooms! – are carefully researched to extract more buck from the same customer. In fact, those experiences are often so well-engineered, we owe them a tip of our marketer’s cap. We’re in relative infancy in that regard.

In online retail, we’re beset somewhat by the “tiny order problem.” Presumably, it isn’t a problem if people come back and buy more later once they’ve acquainted themselves with your business, but it can be frustrating.

(Of course, this is also why Amazon inspires dread among its competitors. From the consumer standpoint, why take a chance on an unknown? So however small or large your brand, by all means you have to establish yourself as a reliable presence.)

An online ad can only do so much. It’s clear that such “larger order encouragement” needs to be part of the overall user experience (eg. contextual recommendations, gamification, etc.) on the website.

Of course, there are a few well-worn incentives to order a bit more, such as free shipping thresholds.

In some cases, there’s a real opening. You might recognize that bulk orders are much more profitable than small orders. Mentioning this in the ad copy might net you a higher order size.

The same principle applies as it does to calls to action. People are probably not going to do what you’d like them to do unless you make it clear that’s what’s expected of them.

Sometimes, your attempts to exact higher or more complex orders will backfire. A high rate of new customer acquisition (even at the low price, loss leader level) might be so important for lifetime value (LTV) that you should focus more on conversion rates than cart sizes. That’s a complex business decision I’m going to have to leave to you.

Wrapping up

Yes, there is a ton of science to creating and testing profitable PPC ads. As an agency dedicated to adroitly managing all significant contributors to profitable PPC accounts, we’ve followed and practiced that science since Google Ads was a baby.

By now, I hope I’ve conveyed at least the flavor of how seriously to take ad testing, how much (or little, in some cases) it can move the needle, and how the strategy and test implementation need to be tailored to each situation. In future installments, we’ll dig more deeply into other aspects of the ad world.

Regardless of format, buyer beware. Big tech is going to make it easier and easier to create all kinds of creative messaging. And it is very fun to consider! For example, Google has rolled out a “bumper machine” that can automatically boil down your longer video into a six-second ad.

Creating cute messages and showing them to people, though, is a far cry from having that budget (yes, it’s a budget) return a demonstrably positive ROI. In fact, if you work with Google reps or a co-worker who “just likes to try everything” (a very common phenomenon for the types of people who want to learn on the company dime), you may want to set aside a specific cap on the percentage of budget and time that get allocated to new formats. You shouldn’t be afraid of shiny objects, but don’t let them take over your life, or your business priorities.

Fundamentals FTW!

Read Part 5: A Misconception About PPC Automation