In SOPPC 21 and 22, I wrote about the various automated “Smart” bidding strategies offered by Google to advertisers who have clear goals and who are looking to save a bit of time managing bids and underlying bid adjustments.

Earlier I also wrote about the prerequisites for this type of bidding to result in positive business results. I must continue to stress: there is no “retire to a spacious villa in the Caribbean” button here, as 99% of investors with $5,000 to plow into cryptocurrency or SPAC’s will undoubtedly find out. “Doing just about as well as everyone else” in business – especially if advertising is an important growth engine for a business – is a formula for generating steady losses on one’s investments. Buy the index in the financial markets if you like – but I wouldn’t think that way in the competitive chess match that is an online ad auction. Don’t just do: outdo.

The fact that there are currently six or seven available Smart Bidding strategies didn’t sit well with me as I thought about what to write, and I expect that came through in my grumpy dismissal of Maximize Clicks and Maximize Conversions, in particular.

Target ROAS and Target CPA are widely used in the industry. Get ready to feel grumpy: they’re going away. Or being “collapsed into” Maximize Conversion Value and Maximize Conversions, to be exact.

Google hasn’t even officially announced it, but everyone knows now that they’ve provided that heads-up on the Developers blog. Hat tip to the eagle-eyed Fred Vallaeys of Optmyzr for bringing that to everyone’s attention.

Google’s claim is that the change won’t affect bidding behavior. No change? Hard to fathom.

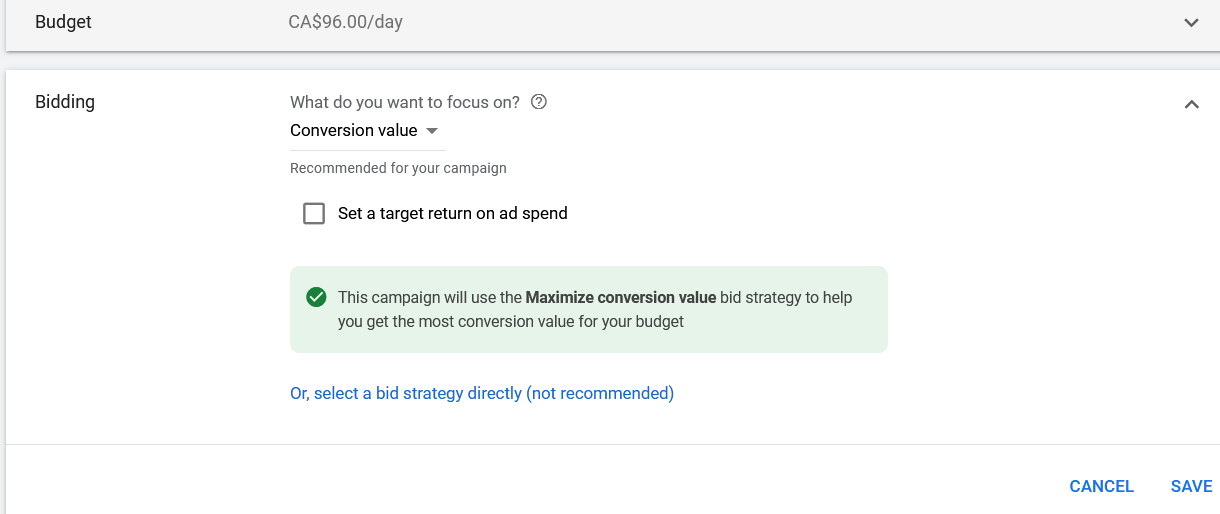

If the old tROAs functionality will still be right there, but accessed through the Maximize Conversion Value strategy, why the change? I can’t imagine, given the opportunity to specify some target range within the Maximize bid strategy setup, why an advertiser wouldn’t provide some target guidance. In reality, there has to be a change afoot, as I’ll explain.

I also feel vindicated in my contention (in SOPPC 21) that Maximize settings with no target guidance were logically incoherent.

I never liked “Maximize” settings because, in the context of achieving business results by spending advertising dollars, the concept of Maximize is shrouded in semantic fog. There is no such thing as open-endedly maximizing this activity without repercussions.

You could “maximize your running speed” by asking to be tied to an accelerating pickup truck, but you’d die after a minute or so. You could “minimize your body fat” with dieting, interval training, and drugs, but below a certain percentage, your organs would give out… and you’d die. (Even many Olympic athletes have body fat in relatively healthy ranges.) Analogous to the advertising example, which won’t really maximize anything: in the first example, to not die, you’d be advised to sprint well above your personal best “only for two or three seconds.” (You’d still be icing your injuries.) And a doctor would tell you how low human body fat can go without causing organ damage, and you’d set a limit several percentage points above that. (Disclaimer: do not try any of the above! This is not a medical or sports training column. Be healthy.)

There is one constraint on your spend when it comes to Maximize settings (of course): your daily budget setting. Google isn’t tying you to the bumper. So now what we’re doing could be named something other than “maximize”. But I guess “generally feel around for performance with no target guidance” doesn’t sound as upbeat.

Feeling around or maximize: whatever you call it, if this genre of bid strategies can find user sessions (a) not too removed from the keyword or Display targeting options you’ve chosen, and (b) highly likely to result in a conversion or revenue, they’ll bid up to improve visibility on those user sessions. If they’re a little less likely to result in a goal, they’ll still court those users, though not as aggressively. Maximize settings are bent on spending your daily budget.

By contrast, if no user sessions seem very likely to achieve a hard ROAS or CPA target under Target ROAS or Target CPA (often abbreviated to tROAS and tCPA by Google Reps, as they must get tired of repeating over and over and over), you’ll find your impression share, spend, and business outcomes from a given campaign or adgroup drifting ever lower.

(So, shortly after sunset of the t-strategies, look forward to new abbreviations from your friends at Google: mConvVal, mConv… etc.)

The new collapsed options will somehow land in the middle of a spectrum of Smart Bidding options that were opaque in the first place. You’ll be able to specify a target CPA or a target ROAS, but these will probably constitute guidelines only. Advertisers will be unlikely to see their spends drifting down and down if the system determines it can’t hit the targets. See the change? This is how “no change” is actually a change.

In any case, the new bid strategies setup may work decently well. If you pay attention to your daily budget settings, and judiciously set ROAS or CPA targets, you’ll be retaining similar functionality to what you had with tROAS and tCPA. But not “the same.”

Figure 1: The setup won’t necessarily look like this going forward, but if there is a box to enter your tROAS guidance, you’d be well-advised to enter that info.

Many others may not be so fortunate. Then again, if they’re not paying attention, who’s to blame for that?

One can imagine that Google assessed the status quo and noticed millions of ad accounts and advertisers who’ve decided to take a contingent approach to their advertising: we’ll only spend a significant amount if the auction can bestow beautiful business outcomes on us. If not, we’re snapping our purse strings tight. With the newly collapsed bid strategies, that rug is pulled out from under those “contingent” advertisers. Want to sit at this poker table? There’s a minimum buy-in.

Many advertisers of this ilk will notice the change and tighten their budgets. Others won’t notice, so that’ll help Google raise prices on less valuable ad inventory.

That being said, for advertisers like you who focus well on the task at hand, the change won’t be too drastic.

To encapsulate it in a formula:

[(tROAS) OR (tCPA)] {are sorta similar to} [the corresponding new m-strategies]

How’s that for crisp and transparent documentation?

Following this shift, advertisers of all shapes and sizes will need to adjust some of their familiar routines as follows:

- First and foremost, daily budget settings must be taken with the utmost seriousness. If there is any question about campaign effectiveness, budgets have to be tightened up. This is where Google expects to increase revenue on the whole. Some advertisers will lower their budgets, but still wind up spending a bit more than they did with their previous, demanding target settings. Many advertisers will fail to adapt, and they’ll spend quite a bit more on low-return advertising.

- Advertisers generally, and in particular those who take care of budgets for smaller, cost-sensitive advertisers, need to begin adopting more guardrails to intervene when the systems aren’t working well for the business. Daily budgets alone don’t constitute a particularly precise measure, as Google doesn’t promise to respect them (only that they’ll be respected over the course of a full month, making daily spend spikes to 3x of budget or more “legit” no matter what the business outcome). Look into scripts or third-party tools that can step in during the day to alert you or to pause campaigns if spend is too far off the daily pace. And if the misbehavior continues, there’s a little thing called manual bidding. Revert to that if you don’t like a bid strategy that gives itself license to “try to spend your budget” with only limited respect for your bespoke targeting choices (keywords, etc.).

So if bombshell feature changes like this – changes with far-reaching implications for media pricing and budget levels – only stand to bump up Google’s revenues for a few months, why would they bother?

Let’s start by giving credit where credit is due: the array of options must have been confusing to the advertiser community. From a user perspective, reducing the number of menu options is probably a sound idea. That being said, Google created that clutter in the first place. Now they’re responding to feedback, presumably.

Google has no doubt modeled the predicted revenue bump from the change.

Three to six months of “oops, some advertisers spent more and got less” is an awfully long time by the standards of these sorts of tweaks. Google’s financials might look materially stronger for two quarters based on the change. When a company is worth a trillion dollars, investor sentiment matters enormously. It can affect employee retention and the price paid for an acquisition. It can fuel, if only indirectly, investments in other letters of the Alphabet.

Beyond that, I have a sneaking suspicion that some other silly bid strategies like Maximize Clicks and Target Impression Share will be noticed more by silly advertisers, and in silly fashion, those advertisers will give Google carte blanche to apply budget to lower-value advertising impressions.

Now you’re all caught up!

Read Part 43: The Impact of Domain Names on PPC Performance