A library cop they call Bookman

Grabbed some beatnik ill-doers and shook them.

Exclaimed Jerry S.,

“I’ll explain this whole mess!”

(But first: this installment from Goodman.)

Funny: many of the best ideas to improve workflow, communications, and optimization within digital advertiser platforms started out as foundational ideas for information architecture on websites long before they became “things” in our marketing workday. As marketers, many of us don’t often work with computer code, and few of us have had formal courses in logic. Even developers of simple websites may have been ahead of us in that regard.

An interesting example is multivariate testing – a technique that cropped up long ago in the process of improving landing page performance as an offshoot of User Experience (UX) science. To this day, the logic behind this kind of testing (with many permutations being tested to attempt to find a “winning formula”) is still struggling to be properly grasped and implemented in the context of text ads, although Google’s Responsive Search Ads environment is indeed a wild and wooly example of multivariate testing.

Well, how about how we organize our account data? In large part, the architecture of digital advertising platforms makes those choices for you. There’s a good reason a lot of people have been able to thrive in Google Ads environment: the way that Google decided to organize campaigns, adgroups, ads, keywords, and queries is pretty helpful to us in keeping everything straight. That’s a powerful and helpful influence on workflow, despite the fact that legions of practitioners do everything in their power to break and abuse the system ☺.

Plus, the ability to slice and dice Analytics data on many different dimensions has long been a top skill of marketers and data analysts. But if we’re not also creating our own custom dimensions from time to time, then we might run into limitations on our analysis or even our basic workflow.

A fix for the fixed taxonomy problem

Years ago, Steve Thomas, the founder of an alternative online directory named Wherewithal, pointed out to us that old-style classification systems, including online directories, lacked flexibility due to the “fixed taxonomy problem.” Google Ads, as I implied above, has a certain fixed way of organizing things. Fortunately, you can add your own special touches to work around this fixed setup if it comes to be a hindrance to advanced analysis.

Thomas’ point made eminent sense in terms of information classification, of course. Once we began to harbor information in a digital environment, as opposed to having to house records in physical card catalogs (or books on shelves), information could be sorted in multiple dimensions, if you will.

As “Web 2.0” and beyond emerged, the notion of “tags” to help users find content became widely practiced in website builds and content management systems. (Twitter and their user base buggered everything up with hashtags, but I digress.) It’s a handy sorting method and it is really as simple and powerful as saying that any entity can carry with it multiple attributes. For example, if (in your website’s content management system) you wanted to sort your product category by price, every product could be tagged with the pricing category (say, $100-199.99). If you wanted to give users the ability to discover every product (or just some products) that use leather as a material, you could go through the effort of creating new tags for that material. In essence, these are non-exclusive categories, so there is theoretically no limit to the richness of new information you might add to help people find things.

Tags are reborn as Labels in Google Ads

One fine day, Google began to allow us to apply tags (these are called Labels in Google Ads) to all the key dimensions of an ad campaign: campaigns, ad groups, keywords, ad creative versions, and even whole accounts. (Big secret now revealed: at Page Zero, I apply the name of the lead account manager as a tag beside each account in our MCC. It feels like we’re in grade school again, and I love it! It’s the little things.)

Let me suggest a few of the ways tags can improve our workflow and our PPC account performance.

First, it’s useful to divide the benefits of Labels into two main categories: communications and optimization.

Using Labels for communication and workflow

In terms of communications and team workflow, Labels can reduce the chaos inherent in collaborating in teams on midsized to larger accounts. Let’s say Alexa, who has been on the team for just over a year now, is tasked with going in and adding three versions of a new style of ad creative to 50 adgroups. (She uses AdWords Editor to do most of the work, including adding the Labels.)

You could do the same with entire adgroups themselves, or keywords. Someone is either tasked with – or takes it upon themselves – to expand an account. Some longer-tail adgroups are added, or additional keywords are folded into existing adgroups based on research. It’s rarely done, but it might not be a bad idea.

In one of our large accounts, I just ran across tags on keywords with only a single-digit number to speak of! (Literally, “3,” “7,” “6,” etc.) Turns out that this historical curiosity of the account represented large batches of keyword adds driven by various phases of keyword research. Why it was useful might be slightly lost in the hazy fog of time, but I interpret it as a healthy reality check on whether certain initiatives represented good return on time spent. Leave breadcrumbs: you’ll sometimes be glad you did.

Accounting for the contributions of different team members is rarely discussed in our field. The assumption is of a lone (“hero”) account manager. If the situation warrants it, team play requires a different mindset. Labels are shorthand, but they are an efficient form of communication.

Using Labels for optimization and account performance

Let’s turn to the more important question of how Labels can help us with analysis and optimization.

When it comes to optimization, we’ve already discussed in past sections how decisive campaign structure can be in certain ways. An unwieldy campaign structure can cause headaches, but a simple campaign structure might not be the be-all and end-all either. In a perfect world, we wouldn’t be overdependent on campaign structure as a decisive factor in how well a campaign is optimized or how readily we can analyze data in the future.

To be sure, there are a lot of ways to analyze data without Labels, by using dimensions available in filters and so forth. (And manual tagging might not always be practical.)

Without Labels, we might be able to do quite a bit, obviously. Let’s say you wanted to review performance of ads by comparing those that contain the call to action “buy now” vs. “buy today” vs. no call to action at all. With some creativity to deal with the “no call to action” element, you should be able to measure each cohort’s performance against the other. (This might be a poor experiment design; I just use it for the purposes of the example.)

More specific theories around ad creative would be harder to measure and isolate, though, using filters only. Let’s say it’s something more abstract: whether or not an ad in a product category lists a few examples of the individual products or not. In this case, a simple filter won’t cut it. Rather, a human analyst would have to be manually tagging ads (Labeling them) with the moniker “Description Ad” or something of that nature. That could become tedious done in perpetuity, but it’s very doable if it’s a theory one would like to measure and optimize to across disparate categories for an entire campaign or two (assuming strong aggregate volume).

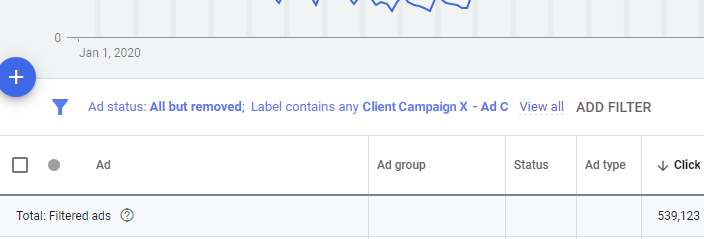

Here’s another example. In one large account, in one of the largest campaigns, we wanted to step back and undertake a systematic re-test of various theories around the ad copy. This test would scale well – there are 140 viable adgroups in this campaign. We broke down the new ad versions into three classes: A, B, and C. One of the introduced ad types involved ad customizers, which I’ll cover in a future piece.

Figure 1: We go into Filters > Attributes > Label to aggregate the performance of every “C version ad” in this campaign.

Labeling the ads in this way as we entered them helped us to assess the overall performance of the new ad versions. Using labels to assess performance across the campaign in this way could provide us with a better interpretation of results than either (i) looking at small-volume results in many of the 140 specific adgroups; (ii) attempting to filter using “ad text contains” a certain word or phrase. When we’re comparing concepts, versions, or attributes that don’t neatly fit into preexisting platform parameters, custom Labels carry the day.

Taxonomy’s no longer so fixed.

And the uses of Labels are mixed.

Color-coded in Pantones

Sweet-treaty, like ringtones(?)

In accounts, they perform some boss tricks!