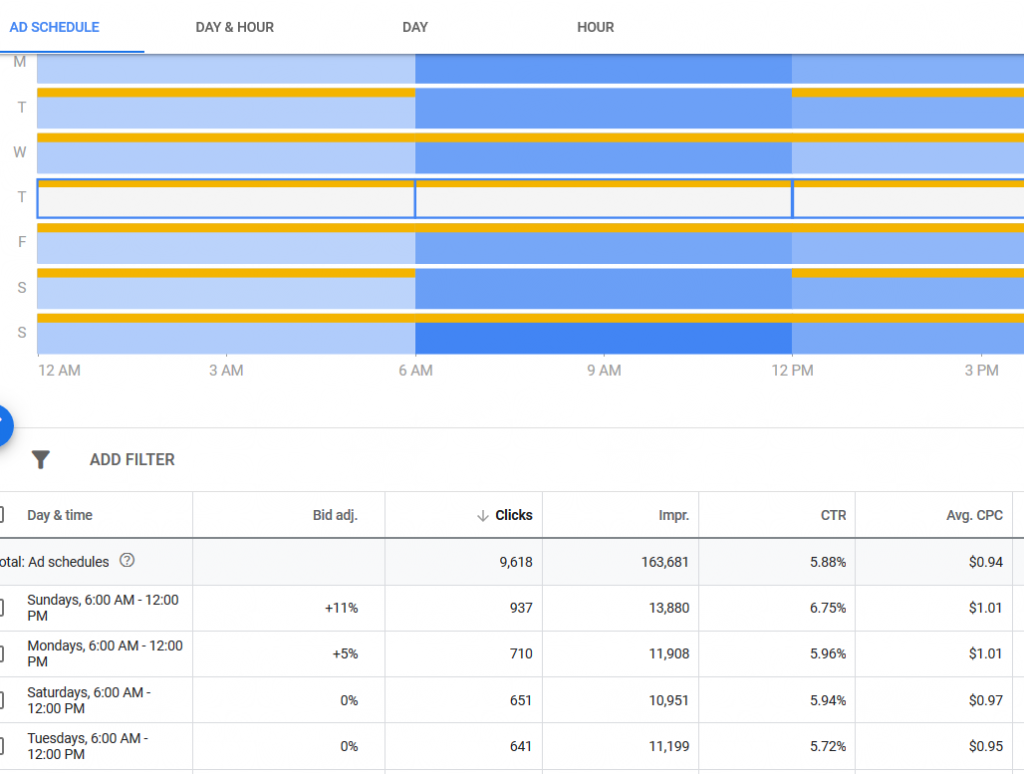

I’m a fan of ad scheduling – always have been. Sometimes called “dayparting,” it’s a Google Ads platform feature that allows you to boost or lower bids for various times of day and days of the week. The platform limits you to six chunks of time per day (times seven, for a total of forty-two chunks per week)—but you might not even need all six. The API also allows more fine-grained bidding, if you wanted to write software to achieve that. You can also turn your ads for certain days or times completely off, at your discretion.

On the whole, dayparting just plain works. But as with any feature, there are some pitfalls that might challenge the logic of dayparting.

Say, if performance is worse at 3:00 a.m. on a Saturday morning, isn’t that person likely to purchase later, when they’re less sleepy? Meh. If they were to purchase later, and we were using a non-last-click attribution model, and we allowed at least 45 days for latent behavior, we’d know it if they did and at least some of the credit would go to that 3:00 a.m. session.

As often as not, if a time period performs worse, it could be a permanent effect. (In other words, they clicked without very high purchase intent, or simply clicked and forgot why they did, and bought a similar product from someone else weeks or months down the road, possibly because someone else was a better fit.) So, I’m going with the hypothesis that we should take our conversion data as literally as possible, and bid as efficiently as we can.

So in the interface, I go through all 35 dayparts I’ve got set up (not 42 in this case) and adjust my bid stance using a large dataset (let’s say, the past six months of campaign history). I’ll generously budget 12 seconds to ponder each operation and 3 seconds to enter the new figure and click the mouse. Multiplied by 35, that comes to 575 seconds.

Q&A:

- OMG! You just spent over eight minutes adjusting all those figures! That’s crazy!??!

- Actually, that wasn’t a question? Anyway, yes. How lazy do you have to be to think that eight minutes of (meaningful) work is onerous?

End of Q&A.

Actually, setting such adjustments isn’t so far off from being a form of automation in its own right. You’re setting up a latticework of rules that govern how the account behaves in different circumstances. This might almost be considered proto-coding. I’d consider it advanced, in the sense that it’s usually neglected. Optimization opportunities that put you one step ahead of the competition are worth chasing after, in my view.

And I’m not ruling out automating this. Ideally, the software would do about the same job as a person, just a little bit better. It would save that person 32 minutes of work per year.

A quick sidebar

Here’s where it starts to get interesting: if that individual had to do this same work to 40 campaigns, that’s over 21 hours of work. That much repetitive work—even spread out over a full year—starts to force choices—namely, one of the following:

- Do the work—it’s only about 90 minutes per month. It may pay off, or it may not.

- Begin neglecting the dayparts, measuring the tradeoff.

- Neglect dayparts on all but the highest-volume campaigns (10 of 40). Now, the annual drudgery meter clocks in at only just over five hours of toil.

- Streamline account structures to eliminate excessive granularity in campaign structure, *and* neglect dayparts on the bottom few campaigns by volume. We’re down to 3-4 hours of annual drudgery.

- For the most part use the same dayparts across all campaigns, based on historical data that show strong tendencies in day and time behavior across all campaigns—basically set and forget—except when it’s glaringly obvious that something is amiss. We’re back down to about 30-40 minutes of eye-stinging busywork per annum.

- Look for or build an automated solution.

So even in the “case of the 40 campaigns,” using “full-fledged automation” isn’t an open-and-shut case.

Back to your regularly scheduled analysis

I’ve built similar tools (with a software developer), and I can tell you that it’s highly likely that the wrong product developer will bake flawed assumptions into any tool like this.

Takeaway: when the time spent is limited, and the result of your work is far-reaching, you’re actually using tools to work more efficiently. On a relatively limited, local scale, that certainly won’t kill you. Indeed, you’ve “proto-coded” – you’ve enacted rules that work when you’re asleep. That might be more than adequate; compared with your competitor, it might be “advanced.”

But then again, we all know that person who buys a lawn tractor to mow a patch of lawn that could probably be cut with scissors (or be just as alluring if replaced with pea gravel). Chacun à son gout.

Read Part 6: Prerequisites for Effective Smart Bidding in PPC