A bit of context for this week’s installment: it may be helpful to reinforce what we’re all about here at Page Zero.

Ever read content by a digital-first company such as Basecamp, GoToMeeting, Zoom, or Dropbox, extolling the virtues of remote work? No one should be surprised that they write about that, since their products are premised on that very thing. They’re simply selling (and, yes, eating) their own dog food.

Analogously, the dog food in question – the service provided by Page Zero – has largely hinged on seeking out various tranches of high-performing ad inventory for the benefit of clients. This requires highly tactical manoeuvres, incremental changes, novel approaches to communications, collaboration, and data analysis, to say nothing of a higher level understanding of client business models, digital channel allocation, user experience phenomena, and so forth. If you boil it down, we’re like a sharply-dressed team of ROI Truffle Pigs.

Our primary channel for capturing this consumer intent is Google. From Day One, the complexity and open-ended architecture of the Google AdWords platform – and competitive and consumer behavior – meant it was always a multifaceted puzzle to solve. The reason for solving it was clear: to benefit clients with measurable financial performance. Our work isn’t performative, it’s “performance-ive.” The playbook we developed over the years allows for seemingly endless variations, but it’s been honed and tested under the harshest and most turbulent of conditions. And it includes plenty of experimentation (even to the point of embracing the concept of mDNA, or “meme DNA” in the natural selection of great ad creative).

Make no mistake: this is a competitive, Olympic-class “business sport.” Outside of reporting and communicating strategy to clients, we don’t vie for style points.

Figure 1: You’re being judged. Good luck!

Where everything is made up and (style) points don’t matter

Unsurprisingly, some people at Google without anything better to do have devised a sort of Style Points System. (There is absolutely no truth to the rumor that Google has packed the panel with Russian judges. Don’t believe everything you read on the Internet!)

Why is this so insidious? Well, of course, because it’s meant to disarm us. To fly beneath our BS detectors. To replace rational thought with subtle compliance cues.

In many fields, we’ve been conditioned to accept aggregate scoring schemes as a means of summing up a more complex picture.

- Your credit score will determine whether or not, and on what terms, you can qualify for a loan. If it’s over 800, you’re golden. If it’s below 500, your car loan may come with a little more, shall we say, friendly surveillance from, er, associates of the lender. Sometimes – it’s true – you can boost that score just by wiping inaccurate information from the file, or paying back an inconsequential debt you’d forgotten about.

- SAT scores, LSAT’s, GMAT’s, and MCAT’s are standardized tests, the scores of which play a large role in granting acceptance to various forms of postsecondary education. Of course, people can study for the tests to improve their odds.

- In pro football, Passer Rating aggregates numerous markers of a quarterback’s skill at the position. This, however, doesn’t correlate tidily with wins and losses. As Coach Tomlin of the Steelers has been heard to say: “The standard is the standard.” The standard dictates that the team’s effort produces a win – little else matters.

At one point in elementary school (think: long before The Simpsons, but well after the heyday of the actual B.F. Skinner), one of our teachers layered a “scoring system” on top of the regular curriculum. We were to receive points based on small tasks, behavior, etc.. The idea seemed to be a gentle means of compliance with norms. There was a leaderboard. It was hinted that there might be some type of pot of gold at the end of this rainbow, but it was never made clear what it would be. We imagined tins of cookies or doubled recess allotments.

As a young person, I was highly competitive, as my mother once remarked after her pride began to give way to a vague sense of dismay. So I was pretty pleased to be hovering near the top of the obedience leaderboard, even though obeying wasn’t really my thing.

One day, my classmate (a former spouse – we were married at age 4) decided to playfully sink a sharpened pencil into my skull. Apparently, an uncensored scream of “awwww, shit!” – hey, at least I didn’t drop any F-bombs – was sufficient to trigger a catastrophic loss of classroom points. It was like 1929 (or 1987) for my brown-nosing portfolio.

Since that day, I’ve taken a skeptic’s view of made-up scoring systems, especially those intended to nudge me in perverse directions counter to my own interest, lifestyle, etc. (I take credit scores very seriously, though! You can’t fight City Hall.)

Let’s turn to Google’s Skinnerian entry into the Scoring System Hall of Shame: Optimization Score.

This is a system that assesses the account management effort in each and every Google Ads account. It’s broken down into handy categories. The more you comply with the recommendations, the closer you creep to a perfect score of 100. Spoiler alert: most of the recommendations are uncorrelated, or negatively correlated with, your company or client’s profit and loss. Unsurprisingly, the very same recommendations may positively impact Google itself. A lot of the recommendations have to do with adopting various automation schemes, which should lead us to a deeper discussion of the nuances of why Google sees it in their interest to constantly harp on adoption of these various types of automation (which we won’t have space for here).

Here’s a walk through a few Optimization Score recommendation categories, with my commentary.

First, The Good News

As longstanding and experienced PPC pros, we’ve often felt like we had to plug our ears and go “la-la-la” when the recommendation engine scolded us with a weak aggregate score that belied the fact that the business and the marketing effort were actually knocking it out of the park.

So I was a little surprised to see a more muted approach evolving.

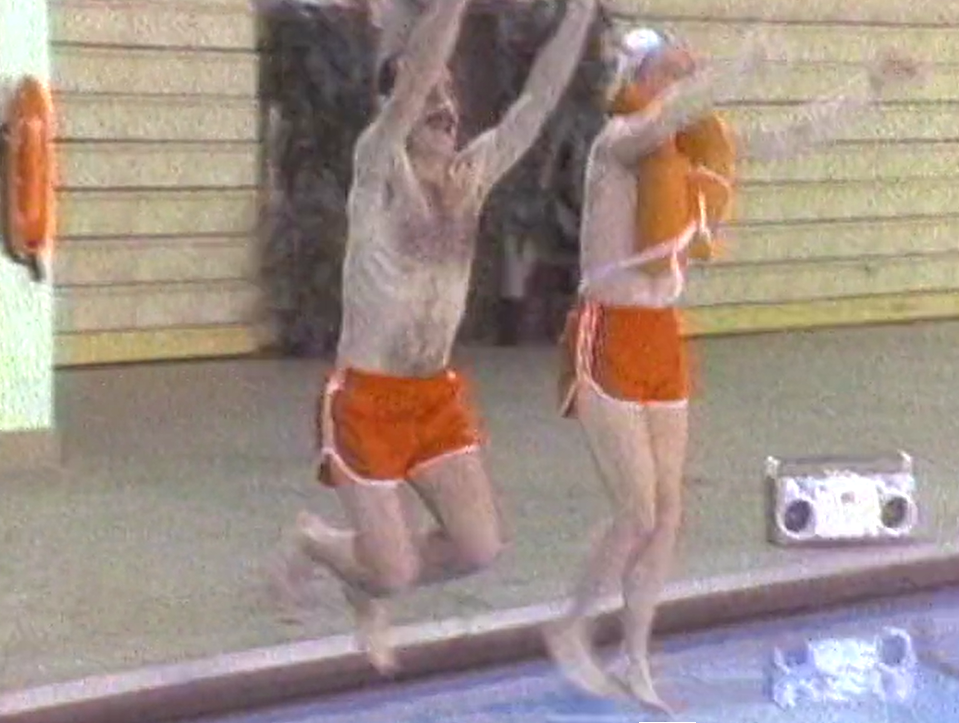

For example, I just checked the account of a small but successful online retailer. The aggregate O-score in the mid-80’s surprised me (I’ve largely hand-built this account myself, with help from colleagues, some automation, plus some third-party tool support), as I tend to ignore stock suggestions. It seems that for the majority of accounts, you get a high score regardless as long as you’ve adopted at least some degree of Smart Bidding (of any kind, including marginal strategies such as Maximize Clicks and Target Impression Share). Hmmmm.

I’m speculating that as long as some of Google’s hobby horses have been fed, they throw you a metaphorically-mixed bone. Or perhaps if I throw the Google Dog enough bones, it lets me get back on my horse and ride like the wind. Anyway…

Consider also that this apparently objective scoring system is open to abuse by its inventor. It could be highly fluid, leading to ever-shifting dissemination of “should do” items. (Not that rigidity is a virtue, but neither is caprice.) At worst, it could be subject to a manual override or at least a deliberate segmentation strategy. Google could, in theory, use this scoring system differently for high-priority (read: high spend) accounts. It’s no secret that Google would rather manage high-spend accounts directly, or at the very least, have much more say in how they’re managed. A bad score drives a wedge between PPC professionals and their clients or bosses. Goliath vs. David. Sorry ‘bout that.

Audiences

The first recommendation in this real-world example, one that would add a whopping 7.6% to the grade, is for an idea I unreservedly like: adding Customer Match audiences to campaigns. This is a type of audience we can use for Remarketing that stems from verified email customer lists (which may be a nice, precise means of targeting past customers and even segmenting them as one often does with large lists of customer email addresses). The effect and reach may be small, but many advertisers like this option. (It’s popular for Facebook as well.)

Figure 2: Have they slipped something in the kibble lately? Is ol’ Google Dog mellowing?

Well, that’s good news. But many other audience recommendations will be superfluous or harmful, which is especially problematic in the hands of the many advertisers who don’t understand how Google defines various types of audiences, what Observation vs. Targeting means, and how differently these work in Display as opposed to Search. The whole tenor of Google’s communications has often been “add a bunch of audiences willy-nilly to campaigns.” We disagree with that approach.

What would we agree with? Better documentation about how audiences work, and better attribution models to properly capture their impact.

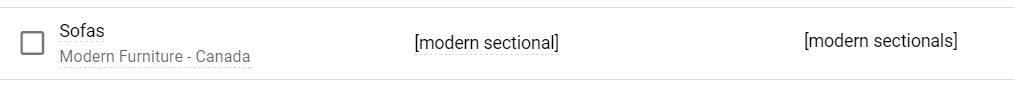

Keywords

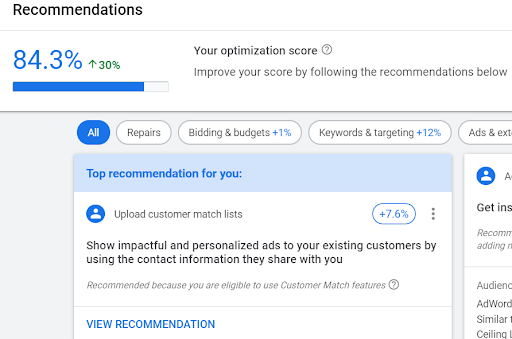

Your strategy to build out campaign, adgroup, and keyword (and match type) structures has to come with a strong spine: a grasp of what you’re trying to accomplish and the pros and cons of various approaches to full or partial coverage of the consumer query universe.

Typical Opty Score keyword and match type suggestions tell you how to get “more exposure” for your business by adding additional keywords or match types. Insidious, for sure!

Indeed, this syncs up with a newbie misconception, which is that we add to the reach of an adgroup or campaign by “adding keywords.” Of course, choosing a different mix of match types, bidding up on bid adjustments or keyword bids, etc. are also ways of getting more impressions or clicks for your campaign.

In this case, the recommendation engine isn’t aware (or doesn’t care) that (a) we’ve already added and observed data from various match types, including broad match modifiers, nor (b) that we are undertaking the difficult task of weeding out “mass market” searches. The problem with the furniture vertical isn’t that we can’t get enough exposure for our business! It’s quite the opposite. By golly we sure do want growth, but generic queries and mass market intent won’t be our ticket to ride. Plus, (c) over time, we’ll have a wealth of performance data to consult in the Search Terms Report. We’ll find many inappropriate matches worthy of negativing out, and occasionally we might light on gems that we’ll want to pull out as specific (additional) keywords to bid on.

Figure 3: Keyword and match type expansion suggestions: sound and fury, signifying very little.

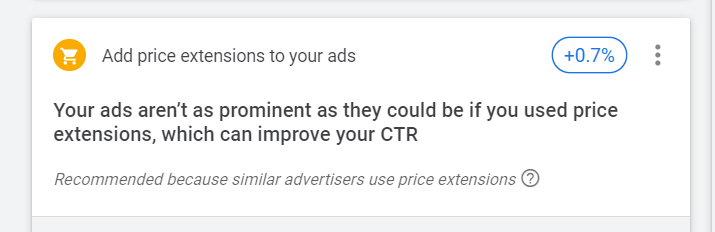

Extensions

We consider it best practice, or at least good practice, to build out an extensive slate of the available ad extensions – especially sitelinks, callouts, and seller ratings. Many of the others do chew up screen real estate, but really are the ultimate in (purely) style points, of little benefit to the consumer or the advertiser. Case in point: price extensions. We will occasionally run experiments with various marginal types of extensions, but we’ve often found the impact of some types of extension to be negligible or even negative.

For this advertiser, the recommendation engine should have been pounding the table on Seller Ratings extensions (the little stars that may show up in an ad unit). Of course, that would be a bit out of bounds, because, quite hilariously (sorry, we PPC’ers have a bone-dry sense of humor), Google has classed Seller Ratings as “automated” extensions – meaning, you have to get them set up on our own by working with an approved ratings service, and Google Ads will automatically decide whether yours are worth showing. Anyway, that one is on the list of must-do’s for this advertiser in 2021. For a new business, there is so much to do, and so little time to do it in. Thus, the unimportant recommendation of adding Price Extensions to campaigns is a distraction, as are most of the marginal recommendations that will help you creep towards your 100% ideal Optimization Score, half a % at a time. Fail.

Figure 4: “Billy Horshaw around the corner grew a handlebar mustache — why don’t you?”

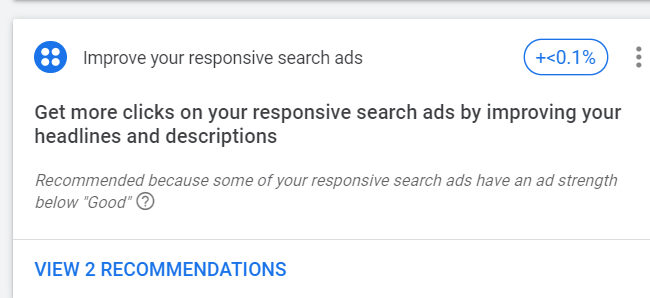

Admittedly inconsequential suggestions

When Google’s own recommendation engine admits you’ll see less than 0.1% improvement in your Optimization Score, you have to wonder why the reco is there in the first place. Human attention spans are finite. Prioritization is key.

In this case, the suggestion is to swap out some mediocre elements in Responsive ad units for some sharper ones that might perform better. Not a bad suggestion at all, but hard to quantify, as Google themselves seem to acknowledge. Firstly, we really have no idea at all what an Ad Strength of “Good” even means in this context (hint: it doesn’t mean ROI). Very little KPI information is provided in Google Ads’ current reporting on the assets and combinations underlying RSA’s (Responsive Search Ads).

Similar suggestions you’ll find around ad copy will include further building out your Responsive Ad units (more headlines, more descriptions), adding more Responsive Ads (did you get the idea Google likes these?), and adding more ad versions of any type to an adgroup’s ad variations in cases where only a single ad is running (never a bad idea, but you already know you paused all the underperforming ads, and are planning to get back to the task of puzzling out new creative in due course).

Several times a year for most businesses, it’s worth setting aside some time to add meat to the ad creative effort. Despite the short format – especially amid attribution (causality) and data interpretation ambiguities, a competitive environment, an extension-cluttered ad display practice by Google, etc., and the difficulty of finding incremental improvements on winning ads once extensive testing has already been done – it’s harder than it looks to create new, meaty ad content. Certainly, that casual automated recommendation seems to be worth the weight Google has assigned it here: < 0.1%. In other words, in the “you already knew this, but…” category.

Figure 5: A trifling < 0.1%.

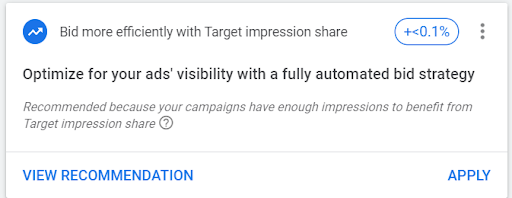

Flummoxing bid strategies

Target Impression Share? Why?

Figure 6: Target Impression Share? Why?!?!

Redundancy is doubleplusungood: make it disappear

“Remove redundant keywords.” This common recommendation counsels us to remove “redundant” keywords with the promise of “making the account easier to manage.” Add keywords, remove keywords, do this, do that! Eep.

The delicious irony is, this “redundancy” exists only in theory, and has only cropped up as an aftereffect of Google changing its matching policies to allow it to violate the old rules for all of broad, phrase, and exact match types. Little matter that we might have data showing that small variations in wording lead to substantial differences in the worth of a query (due to their varying propensity to generate ROI).

Figure 7: Forget bidding on certain “close variations” separately. Google considers them single entities and has stripped you of that control. So why not pretend the better, plural variant, doesn’t even exist?

Leaving the keywords as they were really doesn’t hurt anything.

Ghost them and maybe they’ll get the hint

On the other hand, reading long lists of marginal recommendations does something quite tangible to your productivity: it wastes your time. The charitable assessment of Optimization Score recommendations is to “cherry-pick the ones you find useful, and ignore the rest.” Unfortunately, it isn’t quite that simple. And from the standpoint of objectivity and science, there isn’t much cause to be charitable here. Instead, you might want to hone your professional chops and lean into data analysis, ignoring Optimization Score wholesale.

Read Part 35: The New World of Competitive Metrics: Life After Avg. Pos.