Through LinkedIn, yet another B2B vendor tried to trick me into a “friendly” conversation when all he really wanted was to sell me on the merits of his company’s product: in this case, anti-click-fraud-detection software.

It felt a little like an interaction with Snoopy flying a WW2 bomber. Dogs and generals, and sales reps too young to know how obsolete a product has become, are apparently always fighting the last war.

Malicious activity online is commonplace, needless to say.

And in the subset of malicious activity that involves bots or humans generating clicks or impressions of your ads to cost you money, we have every reason to be vigilant. Such activity has cost advertisers hundreds of millions of dollars over the years.

To this day, the problem is quite bad in the Display advertising world, as I implied last week.

In many ways, digital advertising is not for the faint of heart. Many rip-offs aren’t due to direct abuse, but on the side of weakly-performing media that get propped up by misleading attribution models and reporting. As long as advertisers keep biting on glossy sales pitches and jargon about advanced targeting, AI, and “pay only for ‘performance’!” (all the gimmicks, basically), without setting up reliable vetting (“watchdog” or “checksum”) methods, there will remain incentives to approach advertisers with overpriced offers for non-performing media (even if it isn’t utterly fraudulent).

Example #1: Is It Fraud?

A large e-commerce advertiser – our client at the time – once allocated a trial budget with an exotic retargeting technology – MoltenFace Technologies (the name has been changed). The promise was to exclude existing customers, and to convert more cart abandoners and lookalike style audiences. The idea was to pay only for “performance” on a CPA basis. Now, even though a certain type of view-through impression was supposed to be the measure of that lift, a control study would be done to ensure the lift wasn’t spurious.

I have to hand it to MoltenFace. At least their control study was real. But the number of false starts and spin jobs that happened (including multiple streams of the experiment that each supposedly used a different strategy) on the way to getting a full look at the control study meant six months of costly advertising spend before their bluff was finally called. (You can imagine that by splintering your spend, it might be quite possible to create doubt and even a random winner or two. That’s a trick too!) The sales numbers associated with the experiment group that had been exposed to the wondrous advertising? The lift the ads created? Negative five percent.

Is that fraud? Not exactly. Which may be the point. You have to be vigilant against all kinds of non-performing advertising, not just imagined malicious clicks. Your ad budget is just as badly wasted by BS or shoddy campaign practices as it is by folks or bots maliciously clicking on your ads.

Example #2: Unsophisticated, but Definitely Fraud

We’ve certainly seen our fair share of clever fraud tricks in practice over the years. There are plenty of vulnerabilities in the complex economic models (and user patterns) that make up this ecosystem. In one instance, we took over a campaign for an enterprise B2B client (in email-related software) who was willing to spend around $500-$1,000 for a reasonably qualified lead. It didn’t take long to work out that the previous agency was spending a substantial budget in an unbridled journey through the Google Display Network – and that they were “hitting the target” because bottom-feeder publishers in the network actually hired people to fill in the lead form. A certain number of leads – seemingly almost all of those coming in through that channel – weren’t just poor quality, they were ham-fisted and deliberate attempts on behalf of groups of unscrupulous publishers to ensure that enough forms were submitted on the websites of high-paying enterprise software advertisers that the aggregate cost per lead associated with that publisher site met advertisers’ and Google’s norms. That number was normal. What wasn’t normal was the complete junk content on the forms. (Yes, that could be done in an automated way, but humans can do surprisingly well at it as well.)

When I relate that story to leading ad fraud experts, they laugh, indicating that the methods get significantly more sophisticated than that. So yes, we get it. It’s out there – even though that type of flagrant example would be fairly easy to spot by today’s fraud filters. Caveat advertiser.

Detecting Fraud: Spot the Anomaly

There is relatively little unbiased research available on the subject of click fraud. One study undertaken by a distinguished engineer some years ago studies the problem – and Google’s approach to the problem – in considerable depth before concluding that “Google’s efforts are reasonable.” Amusingly, this study appears to be buried within the archived reading materials on a third-party software vendor who is trying to get you to buy into the idea that Google’s efforts are not reasonable.

There are a variety of methods that can be employed to detect invalid activity on ads. One of them is noting anomalies. If you think about a real person’s behavior vs. a fake clicker’s behavior, the unsophisticated attacks that make up most click fraud are quite easy to stop. Admittedly, it might be harder to catch the drip-drip-drip of occasional fraudulent clicks because they don’t establish a pattern.

If you think in microcosm about simplistic individual strategies to bilk advertisers who pay for clicks directly on Google.com, they don’t get far. First, the activity has to be simply malicious, since the only financial beneficiary of those clicks would be Google, and not a third-party publisher. Competitors might do this to one another, which makes it more feasible that Google’s filters could detect the behavior.

Many clicks by the same or even very similar user on the same advertiser’s ads, especially when triggered by the same types of searches, would eventually be discounted as departing from what real searchers with real intent typically do. (That’s not bulletproof, but undoubtedly the database of anomalous patterns grows richer with time. Machine-learning does indeed work at scale.)

If you want to ask yourself whether Google has the scale to train systems to learn about patterns of spam, you need to look no farther than the search engine itself, which is vulnerable to untold daily volumes of the salty luncheon meat. And if you’ve relied on Gmail, then comparing its spam filter performance (in terms of either false positives or allowing crap through) to an email system with an inferior spam filter, you know that Google has what it takes to take on complex threats and complex security problems – at least to the point of making them low priority for the average decision-maker.

When it comes to the narrow field of click fraud on Google Ads that specifically appear on Search Engine Results Pages (SERP’s), very little has changed in the equation of (1) whether it happens a lot; (2) what third-party solutions can help you do about it; (3) what remedy, if any, is available to you if the sources of the bogus clicks are isolated and documented.

Indeed, very little has changed since this interview of John Marshall by Eric Enge, in which the former – intelligently – alludes to the primary means of managing this for all practical purposes by the business owner: bidding down on the parts of your campaigns that don’t work; excluding placements; allocating efficiently. The other unchanging feature of malicious ad-budget-draining behavior is that slow drips of nearly trivial, hard-to-detect clicking over time are going to be difficult to catch in most every case.

So What Can You Do About It?

As the owner of a website, if you wanted to investigate suspicious activity independently, as click fraud software vendors attempt to do, you’d need access to the data for each raw user session. Such studies will certainly uncover undesirable activity.

However, Google may have already proactively filtered that click (not charged for it). They also claim to continue monitoring patterns and to filter out close cases later on (refund monies). It’s possible to get an accounting of that in your account reporting, though it isn’t detailed. If desired, you can come to Google with evidence of your own to request a click fraud investigation.

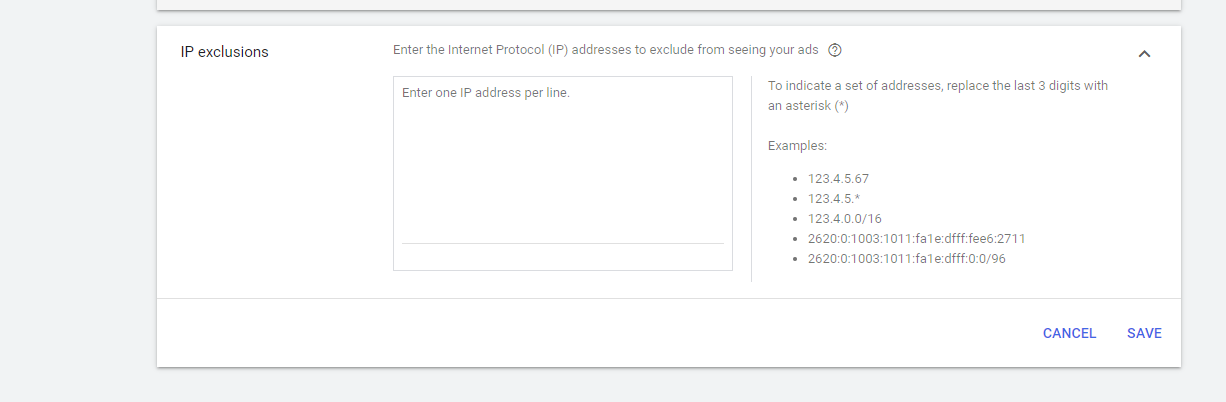

Third-party software? What can it do about whatever weirdness it seems to detect, having no idea what Google has detected or why? Well, it can try to block certain IP addresses from the ad account itself: Google offers this feature in Google Ads.

Some time ago, I had the pleasure of trying to figure out how a third-party click fraud detection software application was actually doing “its job” for a friend’s Google Ads account. The part about combing raw user session data for yucky-looking visits must ultimately be discounted. Various generations of analyzers doing that tend to be so vastly at odds with what Google actually charged for, that advertisers coming to Google with such reports tend to wear out their welcome fairly quickly. And that is really your only solid action item: to ask for a refund. Almost every other non-cap-in-hand approach to combating suspicious activity could be handled with a solid understanding of targeting and reporting.

The remaining activity that the software could help you with would be which IP addresses to exclude. I observed this software quickly reaching the limit of the paltry number of IP addresses Google allowed to be added to a campaign. When it came to the limit, it removed the least recent one and added a new one. The list was always, then, very short. Pretty useless!

Worse than that, it appeared to be excluding whole IP blocks and dynamic IP addresses associated with tens if not hundreds of thousands of home ISP users in my friend’s retail market. The account was not benefiting from the ad fraud detection software: it was struggling to reach a significant number of legitimate prospects. That’s a lot of false positives.

Figure 1: For fun, consider excluding known nasty IP’s, including those of your competitors so they won’t know what your ads are doing. This won’t get you very far, unfortunately.

The True Test of Sincerity

In recent years, at events, in their writings, daily work, software design, and of late, in social media chats and virtual conference events, a few dozen experts came to the fore in our field to work on our most pressing and high-leverage problems. They never talk about click fraud.

I can only assume that this is because “fighting click fraud” effectively is something third-party vendors do as a business model relatively unconnected with the general benefit to advertisers, who allocate their time and budget to high-leverage problems. Google has solved much of this problem. Enough that it doesn’t occupy much of our time. That doesn’t sit well with some people who like to imagine a completely bulletproof system, but I suppose a completely perfect home security system would vaporize the postal carrier. Business is complex.

If you want to determine if an ad fraud expert is really sincere, try this: attempt to engage them in any type of conversation. About this subject matter or anything else. The ones who flee as soon as you aren’t a lead in their “solution pipeline” generally have less experience than they let on, focus on a channel they hope you know less about than they do (and oversell how unique that channel is in comparison with your inferior expertise in all the rest of the channels), and have decided their current line of business will have them make a substantial commission from spurious “percentages of budget” saved by clueless advertisers who gamely trust their budgets with the MoltenFace Technologies of the world, or who can’t even set their campaign geography or keyword match types.

It appears we live in a world of people who let budget slip through their fingers through serious neglect. People who might leave a brand new suite of Herman Miller office furniture by the curb to be stolen by passersby, perhaps. Or the keys to the Lamborghini on the seat, with the door open. Here are your keys and your boardroom chairs, now where’s my $30,000?

Click fraud is big business? Perhaps. Not least for charlatans who can sell you the remedy.

Read Part 33: Is DSA Your Friend? Pros & Cons of Dynamic Search Ads in PPC