We fans of “new media,” as it was once called, have, of course, been brave visionaries.

Among other things, we have felt – nay, proven – that online advertising is typically far less wasteful than traditional broadcast and print advertising. The more measurable a process is, the less wasteful it’s likely to be.

Waste is good business – for some. Just ask Tony Soprano.

As the legend goes, in 2003, the CEO of Viacom took a meeting with the Google founders. He raged at them: “You’re f****ng with the magic!” The magic, of course, being the unmeasurable, glamorous part of the advertising process that created hyperprofits for Big Media and Mad Men alike.

Search engine marketing, of which paid search came to make up a growing share, was different. Instead of puzzling out who to bother with “interruption marketing” (a term coined by Seth Godin), the consumer’s intent would be respected via a response to whatever keywords they typed into the search engine. They ask, they receive. Brilliant, if it works.

Advertising that blends in fairly well with the interface or environment that it shows up in is now buzzworded as “native” advertising. Because search engine marketing is the ultimate example of native advertising, I’ve had trouble instinctively distinguishing what people are calling “native advertising” from all the rest. But I suppose it’s fair to say that a boosted Facebook post is native advertising. It feels like it blends right in with what you’re doing right now, unlike a truck ad during a hockey game. They’re both ways for companies to gain attention and try to win customers, but one isn’t much like the other.

An enhanced or rich business profile on a review site like HomeAdvisor, Yelp, or TripAdvisor is a form of native advertising, although it isn’t really advertising. But it is native.

A website like Zillow – a site to help homeowners buy or sell homes, providing background information like “Zestimates,” or assessments of how much your home is currently worth – arguably tacks on monetization methods that would not be considered native advertising. But the juxtaposition of commercial activity with the user’s search for information is pretty natural. Zillow’s currently worth $10 billion. There are so many functioning business models online today – often, centered around a search for information in a context of commercial intent – that it’s a bit mind-boggling. At $1 trillion, Google is worth an awful lot – 100 times more than Zillow. But then again, when you think about it, $10 billion is pretty good! It’s grown on the back of semi-native something-or-other.

What many of these online models have in common is that their means of monetization – the toll businesses (and uninterested users) pay to increase their level of exposure – is in a context of extreme relevance, and ideally practices something called granularity. (In an attempt to research the latter principle, I punched “90210” into Zillow as my zip code, and came across a lovely home priced at $34.7 million. At 42,000 square feet, and a modern design with reflective glass, it came across like an office building, albeit with a pool and deck chairs. Hopefully you can work from home.)

Intent matters, relevance prevails

A lot of time, a Google searcher has low purchase intent (or none). Their query is, in some form, “informational” – like “can you show me a Euro to USA shoe size comparison chart?” or “how much caffeine in one serving of green tea?” (There is some chance they’re buying shoes, but in my case I was looking to give away or donate shoes. And if they like tea, you know what? Go nuts. Show them a tea ad near the medical caffeine-mgs geekery.)

Formerly, Google used to rank-order the best and most relevant content (a.k.a. the “Ten Blue Links”) in order to help searchers find what they were looking for.

Other times, Google provides its own tool, like a calculator, replicating the functionality you might formerly find somewhere else. Few of us (as users) have a complaint with the idea that Google can provide an instant currency calculation, or help convert an Imperial measure into metric.

I point this out because users don’t care about what either advertisers or “search engine optimization experts” want them to see. Users continue to be delighted by being more adroitly connected with whatever it is they’re looking for.

That means Google still keeps advertisers on a tight leash, and incentivizes them to be relevant – or face rising costs and declining impression shares.

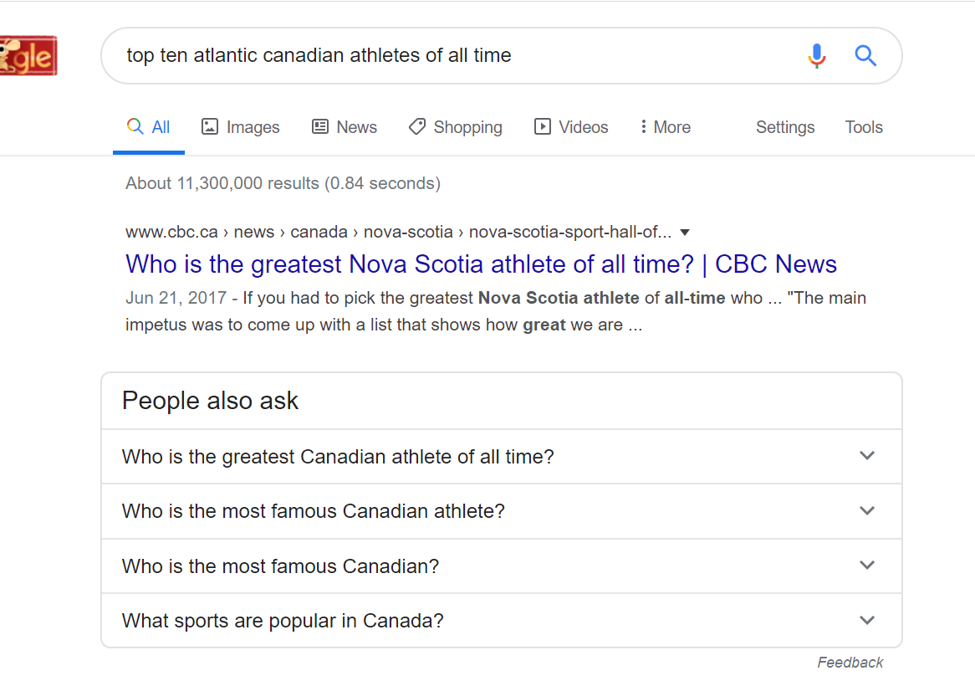

Sure, Google can decide to show ads against even non-commercial queries, some of the time. How does it decide how often to do this? That’s been a moving target. But let’s be clear: Google still focuses on the relevance of both the paid and unpaid portions of their results pages – it’s still their mission. Anytime you get too caught up in a smart circle of people intent on bemoaning the fact that Google makes money and that it’s now all ads, take a few deep breaths and do a few searches. Like this one, the very first one I tried to make this point:

Figure 1: No ads, just a sophisticated effort to show the user relevant content.

In spite of what you’ve been hearing recently, Google still shows a lot of unpaid, informational content on the SERP to people with non-commercial search intent.

Extreme relevance still rules in this realm, even though money is changing hands. And if we love the user, as Google has done (current monopolistic advantages aside, they wouldn’t have been victorious in search market share if they hadn’t been the most user-centric of all the companies in the space), we recognize that relevance leads to user satisfaction, higher clickthrough rates, higher conversion rates, and better ROI.

Relevance gone astray: What not to do

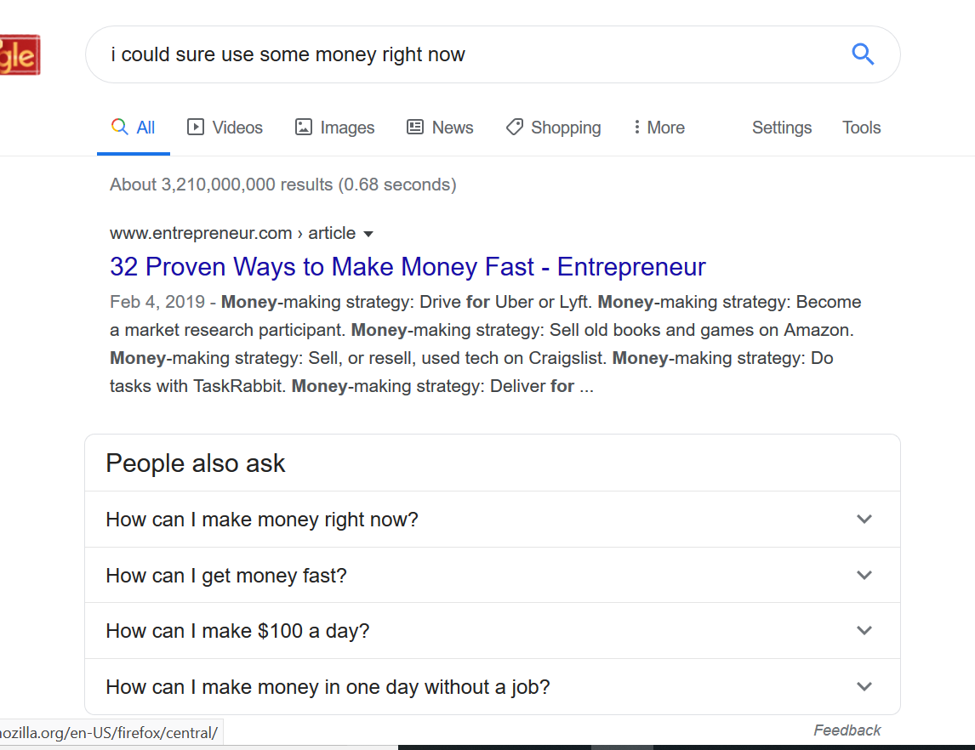

Figure 2: As inane as this search query is, Google won’t bother to allow ads to show against it consistently, because no high-quality advertiser seems willing to create relevant enough campaigns.

In a pay-per-click economy, an advertiser who deliberately spammed the ad auction with particularly tangential targeting would be gaming the system, gaining free impressions and some cheap clicks in less-competitive keyword auctions. As an example, one advertiser at a conference in the UK wanted to show ads against queries for the weekly lottery numbers, in order to generate leads for consumer loans.

In the “you can see this slow-witted logic comin’ up Fifth Avenue” (strolling through Leicester Square?) department, the notion was that someone “needs money” if they searched for “lotto numbers,” so they’ll immediately want to apply for a loan. While we’re at it, why not extend the logic? Every query related to how to repair or sew an existing piece of furniture or garment should be taken as a sign of “needing money,” given that money could help you pay someone to be your lackey. I say, just spam everyone with your offer and hope the offer is persuasive enough.

These are obvious violations of search engine user expectations, so of course Google had to continue refining its Quality Score algorithm in response to the fact that some advertisers will try to bug people who just aren’t interested in what they have to offer.

In Google Ads in particular, strong ad relevance (via clickthrough rates) was rewarded by factoring this into keyword/ad Quality Score. More fuel has been added to the same fire by layering on some additional components of Quality Score: two additional factors called Ad Relevance and Landing Page Experience. Oftentimes, taking users to a highly specific page – eg. the page for Taupe Organic Bamboo Wakeboards (Fresh Scent) – scores highly with the relevance watchdogs. Fine-grained campaign and ad group structure – granularity – is the secret underlying this kind of success. Especially if the search was for “taupe organic bamboo wakeboards with a fresh scent.” Clickthrough rates and ROI alike are probably going to be high in this instance. Compared to that, “our audience is outdoorsy” is an extremely diffuse and ineffective targeting method in the absence of additional cues.

Relevance, meet granularity

“Granularity” in advertising targeting means, if you will, micro-targeting in concert with showing people more specific options in the expectation that they already want something quite specific, so, if you reduce the number of steps and decision points along the route to getting what they already want, they’ll be more likely to purchase.

There are some bits of user experience math that contribute to this body of wisdom, even around landing page selection. (Would you take people to the home page here? A category page? The exact product if they seemingly wanted something specific? The answer seems obvious. It often is. But it often isn’t.) Every additional click may reduce conversion rates by, let’s say, 25%. That oversimplifies issues a lot, but it’s a thing.

Why, nearing the 18th birthday of the day I posted “hello, World, Google has a new, viable version of its pay-per-click program that rewards CTR’s,” do we still need to hammer the basic laws of ad relevance into practitioners’ heads?

Search me.

For whatever reason, for some providers of professional marketing services to this day, relevance seems optional. Wild stabs in the dark seem like fun things to play around with, when all the advertiser and user need is to be connected more directly.

I’ll give you a direct case study of an account I’ve just audited this week, for a new retail brand in housewares. They spoke with us a year ago and said they’d be back if it didn’t work out with their agency.

It’s Google Ads, folks.

By definition, you would think it would be screamingly obvious that the first thing you would do would be to figure out every reasonably straightforward type of keyword search your prospects might perform, so that you could help those searchers buy just that product. Let’s say it’s stemware, even though it isn’t.

This agency, with a sophisticated website that speaks of “optimizing the funnel,” and of course all of the steps along the customer journey, has apparently neglected the stage in the process where you figure out the keywords and the ads and the landing pages that will provide a reasonable chance that the consumer will buy your product.

In the selection of keywords, not to give away specifics, they had tried all kinds of broad-brush sentiments along the lines of “klink” and “let’s celebrate” and “aren’t fermented grapes awesome.”

Then they set up various harmful, nonconverting, money-draining campaigns, and let them run that way for months.

I really couldn’t even begin to speculate as to why.

But it’s for reasons like this that I remind us all that the core wisdom in search marketing does come down to – at least at first – figuring out the obvious parts; relentlessly pursuing the holy grail of relevance.

What are you selling? Are people searching for that?

Can you be even more specific?

Next week, we’ll explore why this necessary core practice still won’t be sufficient for most advertisers.

Read Part 16: How to Broaden your PPC Campaigns